1. Overview

9. Census 2001 and beyond

The United Kingdom in the 21st century is a multifaith society. Everyone has the right to religious freedom. Religious organisations and groups may conduct their rites and ceremonies, promote their beliefs within the limits of the law, own property and run schools and a range of other charitable activities. The 2001 Census included, for the first time in the UK since 1851, a question on religion.

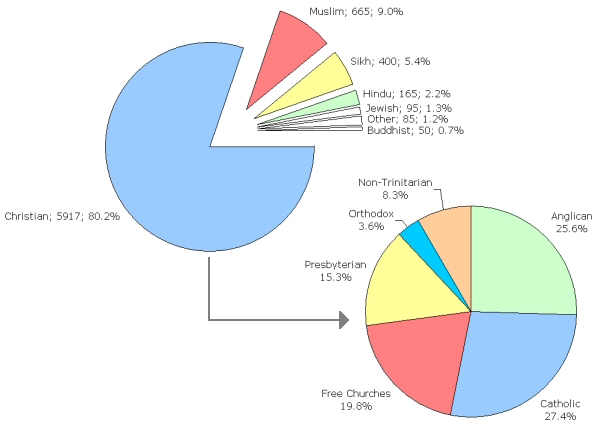

Results of the 2001 Census, active membership figures (Thousands)

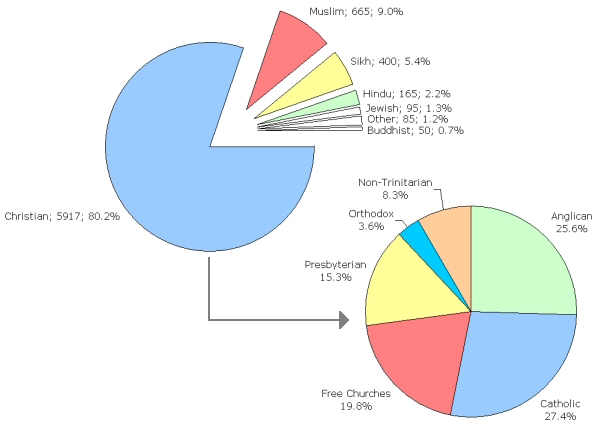

Although the Census 2001 also recorded 390,000 Jedi Knights, making Jedi the fourth-largest 'religion' in the UK, this does not confer them any official recognition. In the latter half of the 20th century, large scale immigration from the Commonwealth countries has led to the introduction of other religions that are practiced by ethnic minorities (see table left below). This has included religions such as Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism and Buddhism. Religions claiming pre-Christian British origins (e.g. Neo-druidism), have some followers, although actual numbers are not known. There is evidence that atheism and agnosticism have grown in the UK over the last 40 years (see table right below); according to a 2004 poll 35% of all residents now consider themselves to be either atheist or agnostic.

Christianity has been the most influential religion in the UK, and it remains the declared faith of the majority of the population. Despite this fact more than 80% of people do not regurarly go to religious services. This definitely does not mean that this vast majority does not believe in God or rejects the existence of any kind of supernatural being, heaven and hell or life after death. According to surveys the majority of the people in the UK certainly has some kind spiritual belief. Two churches have a special status with regard to the State. In England, following the rejection by Henry VIII of the supremacy of the Pope in 1534, the Anglican Church of England has been legally recognised as the official, or established, Church. The Monarch is the ‘Supreme Governor’ of the Church of England and must always be a member of the Church, and promise to uphold it. A similar situation applied in Scotland until the early 20th century regarding the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. (Since then the Church has continued to be recognised as the national Church. The Monarch holds no constitutional role in the government of the Church of Scotland but is represented at the General Assembly in the office of the Lord High Commissioner.) There are no ‘established’ churches in Wales or Northern Ireland. In Wales, the Anglican Church is known as the Church in Wales.

A distinction is often drawn between ‘community size’ figures and ‘active membership’ figures, with the former representing identification with a religion (or a religious ethic in the broadest sense) and the latter a much closer association. Current community size estimates suggest 40 million people (67%) in the UK identify themselves as Christians. On the same basis it is estimated that there are over 1.5 million Muslims (2.6%); around half a million Hindus (0.8%), half a million Sikhs (0.8%), and nearly a third of a million Jews (0.5%). In addition to the 8 million active faith members of religions, many other people participate in formal religious ceremonies at times of crisis or for significant events such as birth, marriage and death.

The Church of England is part of a worldwide Communion of Anglican churches, 38 in all, with a UK membership of 1.7 million. The Presbyterian Church of Scotland has an adult membership in the UK of over 600,000. The Catholic Church has the largest active adult membership of any single Christian denomination in the UK, with average weekly Mass attendance of over 1 million in England and Wales and 225,000 in Scotland. The rise of the Puritan movement in the 16th and 17th centuries led to a proliferation of nonconformist churches. The term ‘Free Churches’ is often used to describe those Protestant churches in the UK which, unlike the Church of England and the Church of Scotland, are not ‘established’ churches. The major Free Churches include Methodist, Baptist, United Reformed, Salvation Army and Pentecostal churches. The British Methodist Church, the largest of the Free Churches, originated in the 18th century following the evangelical revival under John Wesley (1703–91). It has 332,000 adult full members. The present Church is based on the 1932 union of most of the separate Methodist Churches. The Baptists first achieved an organised form in the UK in the 17th century. Today they are mainly organised in groups of churches, most of which belong to the Baptist Union of Great Britain with about 145,000 members. There are also separate Baptist Unions for Scotland, Wales and Ireland, and other independent Baptist Churches. The third largest of the Free Churches is the United Reformed Church, with some 93,000 members. It was formed in 1972 from the union of the Congregational Church in England and Wales with the Presbyterian Church in England. More recent developments within the Christian tradition have included the rise of Pentecostalism and the charismatic movement. The Christian ‘house church’ movement (or ‘new churches’) began in the 1970s when some of the charismatics began to establish their own congregations. The movement, whose growth within the UK has been most marked in England, is characterised by lay leadership and is organised into a number of loose fellowships.

In addition to Christianity, the United Kingdom is also home of many other world religions.

§ A significant Muslim community has existed in the UK since Muslim seamen and traders settled around the major ports in the early 19th century. Most came from the Middle East and the areas that are now Pakistan and Bangladesh. There was further settlement after the First World War, and again in the 1950s and 1960s as people arrived to meet the shortage of labour following the Second World War. The 1970s saw the arrival of significant numbers of Muslims of Asian origin from Kenya and Uganda. There are also well-established Turkish Cypriot and Iranian Muslim communities, while more recently Muslims from Somalia, Iraq, Bosnia and Kosovo have sought refuge in the UK. There are smaller numbers of English and West Indian Muslims. In total, there are around 1.5 million people who identify themselves as Muslims in the UK, the majority of whom are now British-born.

§ Most of the Sikh community in the UK are of Punjabi from East Africa and other former British colonies to which members of their family had migrated, but the majority have come to the UK directly from the Punjab. There are between 400,000 and 500,000 members, making it the largest Sikh community outside the Indian subcontinent.

§ The Hindu community in the UK originates largely from India, although others have come from countries of Africa to which earlier generations had previously migrated (Kenya, Tanzania, etc.). The number of members is close to 1 million.

§ Jews first settled in England at the time of the Norman Conquest. They were expelled by Edward I in 1290, but readmitted during the Cromwellian Republic (1642–51). Sephardic Jews, who originally came from Spain and Portugal, have been present in the UK since the mid-17th century. The majority of the 300,000 Jews in the UK today, while British born, are Ashkenazi Jews, of Central and East European origin, who fled persecution in the Russian Empire between 1881 and 1914, and Nazi persecution in Germany and other European countries from 1933 onwards.

§ The Buddhist community in the UK has around 50,000 followers, both of British or Western origin, and of South Asian and Asian background.

§ Other religious groups in the UK were originally founded in the United States in the 19th century. These include the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (the Mormon Church, with about 180,000 members in Britain), the Jehovah’s Witnesses (146,000 members), the Christadelphians, the Christian Scientists. The Spiritualists have about 35,000 members. These religious groups claim to be Christians, even sound Christian, but do not acknowledge the Holy Bible (instead have their own, modified version), as well as teaching that only those belonging to their churches will go to heaven (Anglicans, Catholics, Baptists, Methodists etc. will not).

§ A number of newer, non-Christian religious movements, established since the Second World War and often with overseas origins, are now active in the UK. Examples include the Church of Scientology, the Transcendental Meditation movement, the Unification Church and various New Age groups.

|

A new use has been found for Anglican church steeples. Mobile telephone companies have, by agreement with individual parishes, recently placed telephone aerials on a number of church steeples, generating income in the form of annual rent for the churches concerned. |

Besides its spiritual importance, the religious architecture of the United Kingdom includes buildings of importance to the tourism industry and local pride. The State does not contribute to the general expenses of church maintenance, although some state aid does help repair historic churches. For examle in 1999–2000 English Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund jointly offered grants to churches totalling £26 million. Assistance is also given to meet some of the costs of repairing cathedrals, and £3 million was available from English Heritage in 2000–01. The Churches Conservation Trust, funded jointly by the Government and the Church of England, preserves Anglican churches of particular cultural and historical importance that are no longer used as regular places of worship. At present over 300 churches are maintained in this way. The Historic Chapels Trust was established to take into ownership redundant chapels and other places of worship in England of outstanding architectural and historic interest. Buildings of all denominations and faiths can be and have been taken into care, including nonconformist chapels, Catholic churches, private Anglican chapels and synagogues.

Although

religious buildings are not as central to Buddhist life as to that of other

religious traditions, there are some 50

Buddhist monasteries (on the picture: Buddhist Vihara, Wolverhampton) and temples in the UK.

Although

religious buildings are not as central to Buddhist life as to that of other

religious traditions, there are some 50

Buddhist monasteries (on the picture: Buddhist Vihara, Wolverhampton) and temples in the UK.

The first Hindu temple, or mandir, was opened in

London in the 1950s and there are now over 140 mandirs in the UK; many are

affiliated to the National Council of Hindu Temples (UK). The Swaminarayan Hindu

Temple, in north London (on the picure), is the first purpose-built Hindu temple in Europe, having a large cultural complex with

provision for conferences, exhibitions, marriages, sports and health

clinics.

The first Hindu temple, or mandir, was opened in

London in the 1950s and there are now over 140 mandirs in the UK; many are

affiliated to the National Council of Hindu Temples (UK). The Swaminarayan Hindu

Temple, in north London (on the picure), is the first purpose-built Hindu temple in Europe, having a large cultural complex with

provision for conferences, exhibitions, marriages, sports and health

clinics.

Jewish synagogues in the UK number slightly fewer than 300, a lower figure than

the number of congregations (on the picture Wolverhampton Synagogue

building).

Jewish synagogues in the UK number slightly fewer than 300, a lower figure than

the number of congregations (on the picture Wolverhampton Synagogue

building).

There

are over 1,000 mosques and numerous community Muslim centres throughout the UK

(left: Finsbury

Park, London; bottom: Regent Park). Mosques are not only places of

worship; they also offer instruction in the Muslim way of life and facilities

for education and welfare. Mosques range from converted buildings in many towns

to the Central Mosque in Regent’s Park, London, and its associated Islamic

Cultural Centre. The main cities in the Midlands, North West and North

East of England, and in Scotland also have their own central mosques with a range of community facilities.

There

are over 1,000 mosques and numerous community Muslim centres throughout the UK

(left: Finsbury

Park, London; bottom: Regent Park). Mosques are not only places of

worship; they also offer instruction in the Muslim way of life and facilities

for education and welfare. Mosques range from converted buildings in many towns

to the Central Mosque in Regent’s Park, London, and its associated Islamic

Cultural Centre. The main cities in the Midlands, North West and North

East of England, and in Scotland also have their own central mosques with a range of community facilities.

The largest gurdwara, or Sikh temple, in the UK is situated in Southall, Middlesex

(on the picture). Gurdwaras serve the

religious, educational, welfare and cultural needs of their community. A granthi is usually employed to take care of the building and to conduct

prayers. There are over 200 gurdwaras in the UK, the vast majority being in

England and Wales.

The largest gurdwara, or Sikh temple, in the UK is situated in Southall, Middlesex

(on the picture). Gurdwaras serve the

religious, educational, welfare and cultural needs of their community. A granthi is usually employed to take care of the building and to conduct

prayers. There are over 200 gurdwaras in the UK, the vast majority being in

England and Wales.

The influence of Christianity and other religions in the UK has always extended far beyond the comparatively narrow spheres of organised and private worship. Religious organisations are actively involved in voluntary work and the provision of social services - many schools and hospitals, for example, were founded by men and women who were strongly influenced by Christian motives. Easter and Christmas, the two most important events in the Christian calendar, are the year’s major public holidays. Festivals and other events observed by other religions - such as Diwali (Hindu), Ramadan (Muslim), Vaisakhi (Sikh) and Passover (Jewish) - are adding to the visible diversity of life in the UK today. The moral codes of behaviour associated with many religions have helped to determine how young people are educated. The way individuals dress, eat, express themselves artistically and view themselves as belonging to an immediate community can often be derived from, and inspired by, a particular religious tradition.

Art

All major world religions have been a rich source of inspiration for art and artists, and interest in religious art shows no sign of losing ground. ‘Seeing Salvation’, a major exhibition held in the National Gallery in London, was the most visited show in 2000 of all the major galleries and museums of Great Britain, and the fourth most visited in the world. There was an exhibition ‘Arts of the Sikh Kingdoms’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1999 and one on Jainism in 1998. Regular annual events such as the Islam Awareness Week help to promote the social, cultural and artistic contribution of British Muslims.

Religious Education

In England and Wales all state schools must provide religious education, each local education authority being responsible for producing a locally agreed syllabus. Syllabuses must reflect Christianity, while taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in the UK. State schools must provide a daily act of collective worship. Parents may withdraw their children from religious education. The vast majority of the maintained schools that have a religious character are either Anglican (nearly 4,700 schools) or Catholic (around 2,100 schools). In addition, there is a well-established tradition of Methodist and Jewish schools, with about 30 schools provided by each. Recently the Government has helped set up, and given support to, a number of schools reflecting other religious traditions - Greek Orthodox, Muslim, Seventh-day Adventist and Sikh. All the churches and faith groups involved with the provision of these schools have organisations at national or regional level to provide support and help when opportunities arise to promote new schools.

In Scotland, education authorities must ensure that schools provide religious education and regular opportunities for religious observance. The law does not specify the form of religious education, but it is recommended that pupils should be provided with a broad-based curriculum, through which they can develop a knowledge and understanding of Christianity and other world religions, and develop their own beliefs, attitudes and moral values and practices.

In Northern Ireland a core syllabus for religious education has been approved by the main churches and this must be taught in all state schools. Integrated education is encouraged and all schools must be open to pupils of all religions, although in practice most Catholic pupils attend Catholic maintained or Catholic voluntary grammar schools, and most Protestant children are enrolled at controlled schools or nondenominational voluntary grammar schools. However, the number of inter-denominational schools is increasing. In 2000–01, over 13,800 primary and secondary school pupils received their education at ‘integrated’ schools not attached to any particular religion (10% of students).

Welfare

|

December 2000 saw the end of the Jubilee 2000 coalition in the UK, a group of over 100 national and regional organisations, including many churches and other religious groups. It campaigned for 100% cancellation of the debts of the world’s poorest countries and was influential in persuading the G7 countries to promise to do so. |

Charitable concern is a feature of many religions. There are currently over 3,000 charities with religious connections helping to translate charitable concern into charitable action, usually involving some sort of practical or financial help given by the charity to those in need. Around two-thirds of such charities have a Christian connection, such as Oxfam or CAFOD, but there are also many Jewish and Islamic charities operating within this sector. Muslim Aid and Islamic Relief are two British Muslim charities that organise appeals and deliver relief aid globally. Within the UK the Salvation Army is the largest, most diverse provider of social services after the Government. It is one of the biggest providers of hostel accommodation, offering over 3,000 beds every night. Other services include work with alcoholics, prison chaplaincy and a family-tracing service which receives 5,000 enquiries each year. The Quakers have a long tradition of social concern and peacemaking.

Buddhism

The First Noble Truth: Life consists of suffering; everybody experiences pain, misery, sorrow and unfulfillment.

The Second Noble Truth: Everything is impermanent and ever-changing. We suffer because we desire those things that are impermanent.

The Third Noble Truth: The way to liberate oneself from suffering is by eliminating all desire.

The Fourth Noble Truth: Desire can be eliminated by following the Eightfold Path:

1. Right understanding

2. Right thought

3. Right speech

4. Right action

5. Right livelihood

6. Right effort

7. Right awareness

8. Right meditation

Islam

1. God (Allah) is one and no partner is to be associated with Him.

2. God has sent prophets (most are unknown, but many include biblical characters e.g. Noah, Abraham and Jesus) to every nation to preach His Message, but Muhammad is the only prophet who is for all time and for all people.

3. There will be a day when all will stand before Allah in judgement. Each person's deeds will be weighed in the balance. Those whose good deeds outweigh their bad deeds will be rewarded with Paradise; and the other group will be judged to hell.

4. The obligations of Islam to ensure your salvation include the following:

I. To Recite the Shahadah: when reciting the Shahadah, one says: 'I bear witness that there is no God but Allah and that Muhammad is His messenger.'

II. To Pray: seventeen cycles of prayer each day, spread over five times of prayer during the day; facing Mecca

III. To Fast: During Ramadhan Muslims are expected to fast (no food, no drink, no smoking, no sex) during the daylight hours. After sundown it is allowed to partake the listed things until sunrise.

IV. To Give Alms: Muslims are commanded to give one-fortieth (2.5%) of their income to the poor.

V. To Make a Pilgrimage: to Mecca at least once during his or her lifetime.

Hinduism

1. The ultimate Reality (Brahman) is an impersonal oneness that is beyond all distinction, including personal and moral distinctions. The universe is continuous with and extended from the Being of Brahman.

2. Our true selves extended from the one with Brahman. Our essence is identical to that of the essence of Brahman.

3. Humanity's primary problem is that we are ignorant of our divine nature. We have forgotten that we are extended from Brahman and we have attached ourselves to the desires of separate selves. Because of the ego's attachments to its desires and individualistic existence, we become subject to the law of karma. The effect of our actions, determined by the karma, follow us not only in the present lifetime, but from lifetime to lifetime (reincarnation).

4. We are reaping in this lifetime the consequences of the deeds we commited in previous lifetimes. A persons's karma determines the kind of body - whether human or animal - into which he or she will be reincarnated in the next lifetime.

5. The solution is to be liberated from the wheel of life, death and rebirth. Such liberation is attained through realizing that the concept of the individual self is an illusion and that only the undifferentiated oneness of Brahman is real. With such a realization in mind, one must strive.

Christianity

1. God is the creator of the universe; personal, omnipotent, omnipresent, righteous but gracious.

2. God loves every person and offers a wonderful plan for everyone's life.

3. Mankind is sinful and separated from God. Therefore, people cannot know and experience God's love and plan for their life.

4. Jesus Christ is God's only provision for people's sin. Through Him (by His death on the Cross and ressurection from death) everyone can know and experience God's love and plan for their life.

5. Anyone who individually receives Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord; can know and experience God's love and plan for his/her life.

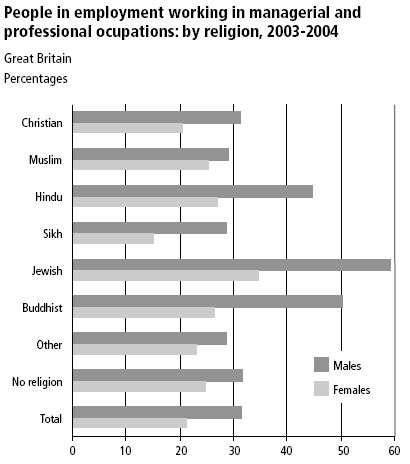

Religious background influences several aspects of everyday life. These 'cause and effect' patterns can be revealed by socio-metric investigations.

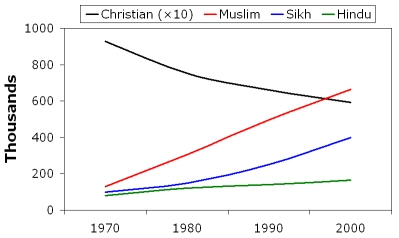

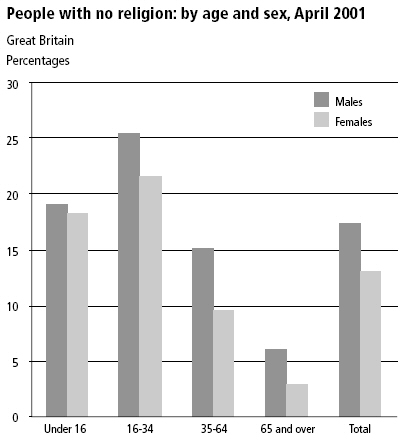

Age and Sex distribution

§ Muslims have the youngest age profile of all the religious groups in Great Britain. Muslims are the only religious group in which men outnumber women – 52 per cent compared with 48 per cent. This reflects the gender structure of Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups, in which men slightly outnumber women due to their immigration history.

§ Younger people are more likely than older people not to belong to any religion, reflecting the trend towards secularisation.

Geographic distribution

§ People from non-Christian religions (in 2001) made up 6 per cent of the population in England, compared with only 2 per cent in Wales and 1 per cent in Scotland.

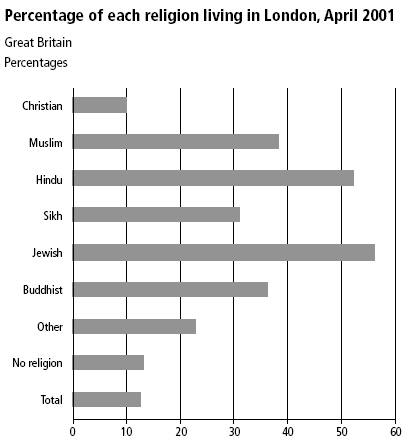

§ People from Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim and Sikh backgrounds were concentrated in London and other large urban areas. Christians and those with no religion were more evenly dispersed across the country.

§ The Jewish population was the most heavily concentrated in London, with 56 per cent of the Jewish population of Great Britain living there. Almost one in five Jews (17 per cent) lived in the London Borough of Barnet, where they constituted 15 per cent of the population.

§ Just over half (52 per cent) of Britain’s Hindu population lived in London.

§ Christians were spread across Britain. London had the lowest proportion of Christians – only 58 per cent of the London population described themselves as Christians.

Country of Birth and National Identitiy

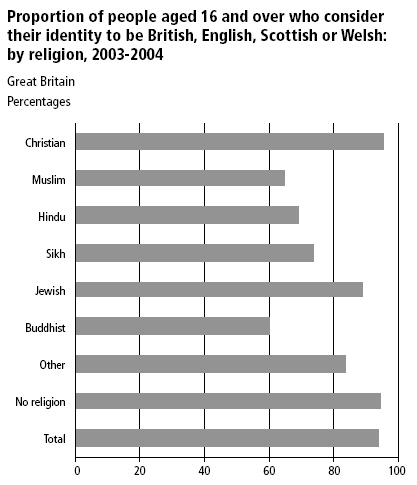

§ In every religious group the majority of adults aged 16 and over in Great Britain described their national identity as either British, English, Scottish or Welsh.

§ National identity is strongly related to the country of birth. Adults from all religious groups who were born in the UK were more likely than their foreign-born counterparts to give a British identity.

§ Almost all (99 per cent) UK-born Jews, Christians and people with no religion had a British national identity (as opposed to English, Scottish or Welsh). Nine out of ten UK-born Buddhists (94 per cent), Muslims (93 per cent), Sikhs (90 per cent) and Hindus (91 per cent) gave a British national identity.

Marriage Patterns

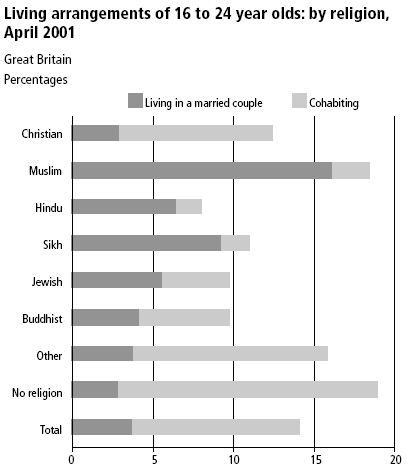

People with no religion were the most likely to be cohabiting (16 per cent of 16 to 24 year olds). They are followed by those 'Christians' who fall quite far from the Biblical standards concernig this matter. Young Muslim adults were more likely to be married (22 per cent) than were young people from any other religious background. Overall, Hindus and Sikhs are the least likely to be divorced, separated or re-married. The range of the graph below also suggests that the main stream of marriages is above 24.

Households

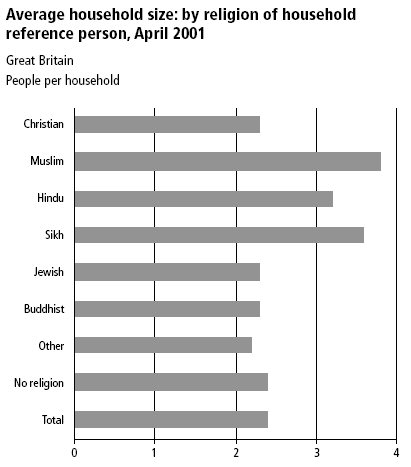

§ Muslim, Sikh and Hindu households in Great Britain are larger than households headed by someone of another religion. In 2001, households headed by a Muslim were the largest, with an average size of 3.8 people, followed by households headed by Sikhs (3.6 people) and Hindus (3.2 people). A third of Muslim households (34 per cent) contained more than five people, as did 28 per cent of Sikh and 19 per cent of Hindu households.

§ Jewish, Christian and Buddhist households were smaller – each with an average size of 2.3 people.

§ Over 30 per cent of these households contained only one person, compared with between 13 and 15 per cent of Sikh, Hindu or Muslim households.

§ Muslim households also contained the highest number of children. A quarter (25 per cent) of Muslim households contained three or more dependent children, compared with 14 per cent of Sikh, 7 per cent of Hindu, and 5 per cent of Christian households.

§ Lone parent households are less common within Muslim, Hindu, Sikh or Jewish communities.

Education

§ In January 2003 there were almost 7,000 state-maintained faith schools in England, making up 35 per cent of primary and 17 per cent of secondary schools. The overwhelming majority of these faith schools (99 per cent) were Christian.

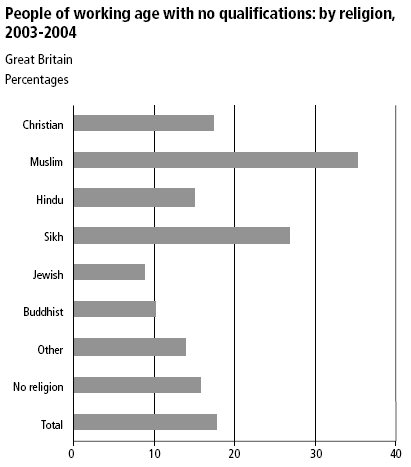

§ In 2003-2004, almost a third (31 per cent) of Muslims of working age in Great Britain had no qualifications – the highest proportion for any religious group. They are also the least likely to have degrees.

§ After Muslims, Sikhs are the next most likely to have no qualifications, followed by Christians. Around a quarter (23 per cent) of Sikhs and 15 per cent of Christians had no qualifications. Overall, Sikhs are as likely as Christians to hold degrees (16 per cent in each group in 2003-2004), and young Sikhs are more likely than Christians of the same age to do so. The pattern is reversed among older age groups.

§ Jews and Buddhists, followed by Hindus, are the most likely to have degrees. A third of Jews and Buddhists (37 and 33 per cent respectively), and a quarter (26 per cent) of Hindus, had a degree.

Labour market

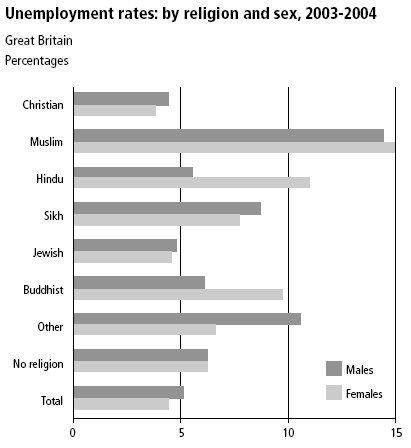

§ Tightly connected to the previous comparison, unemployment rates for Muslims are higher than those for people from any other religion, for both men and women.

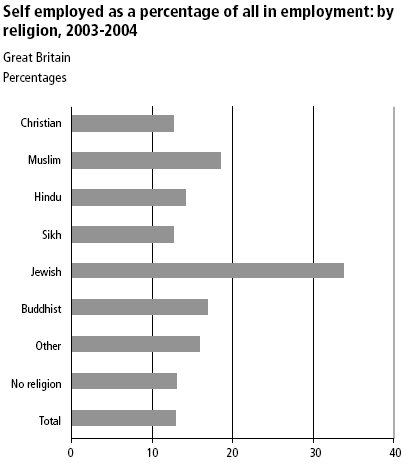

§ Jewish people were most likely to be self-employed in Great Britain in 2003-2004, followed by Muslims.

§ Certain religious groups are concentrated in particular industries. In 2003-2004, 40 per cent of Muslim men in employment were working in the distribution, hotel and restaurant industry compared with 17 per cent of Christian men and no more than 29 per cent of men in any other group.

§ Muslims, together with Sikhs, were more likely than other men to be working in the transport and communication industry. More than one in seven from these religions worked in this sector compared with less than one in ten from any other religious group.

§ Jewish men were more likely than men from any other religion to work in the banking, finance and insurance industry. Around a third of Jewish men worked in this sector.

|

Established Church |

államegyház, államvallás |

sources:

National Statistics, UK 2002, The Official Yearbook of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Wikipedia, Religion in the United Kingdom

Dean C. Halverson: The compact guide to world religions

Focus on Religion, National Statistics publication 2004

Overview:

extracted from Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia under GNU Free Documentation Licence.2-7 chapters: extracted from The Official Yearbook of GB and NI © Crown Copyright 2001, under PSI licence

Census 2001 and beyond

extracted from Focus on Religion © Crown Copyright 2004, under PSI licence