Murals in Northern Ireland

written by Neil Jarman

![]()

"In little more than a decade mural painting has developed into one of the most dynamic media for symbolic expression in the north of Ireland. On any journey, real or virtual, through the working-class estates of Belfast one is bombarded by a panoply of visual statements. In recent years these images have become increasingly elaborate and extensive in their design and professional in their execution. Nowadays scaffolding is often erected in front of walls which are to be transformed and painters may spend days working to cover a wall with symbols, icons and images. We have come a long way from 1970 when two men were sentenced to six months' imprisonment for painting a tricolour - the flag of the Irish Republic, the strongest symbol of Irish Catholic nationalism - or from 1980 when a 16-year-old youth was shot dead while painting republican slogans on a wall by a policeman who said he thought the paintbrush was a gun. Nowadays such activity is largely acknowledged as an established, if not entirely legitimate, political practice.

"Mural painting has been a feature of unionist popular culture since the early years of this century when images of King William III and other Orange symbols began to adorn the gable walls of the working-class areas of Belfast. They appeared as part of an assertion of the Protestant people's sense of British identity during an extended period of political crisis. In the later stages of the Home Rule campaign and, following partition in 1921, in the period of consolidation of the Northern Irish state, mural paintings were used to complement and extend the existing forms of Orange displays."

"The power of the murals have meant that they have become a more self-conscious means by which to propagandise to a much wider public, while still primarily aimed at a local audience. For the global media these remain little more than relatively simple symbols of the Troubles and of paramilitary violence. On the other hand the local media have begun to recognise the significance of the paintings, although they are not always sure how seriously to treat them. The local press now frequently reports the appearance of a new mural as a news item in itself. While they are still rarely prepared to analyse the message as offering an insight into paramilitary thinking"

"While historically most murals have been painted to be seen from within the community of support, these recent paintings seem to be used more clearly to look out, beyond the community and into the wider society."

"For tourists, many of the murals may suggest a romanticised view of the violence of recent years, even a nostalgia for the imagined sense of community which has provided the base for resistance and struggle, and at times encouraged sacrifice for the cause. For the communities themselves the walls have long been regarded as an appropriate place on which to honour and remember the dead and imprisoned. The working-class areas contain many small memorials which record the names of local individuals who have been killed during the Troubles." In most cases it is easy to tell which community a mural belongs to (Republican or Loyalist) simply by the flags and the dominant colours used by the artists as well as by the symbolism present on the pictures.

Nationalist murals (= Republican, "anti-UK")

|

|

|

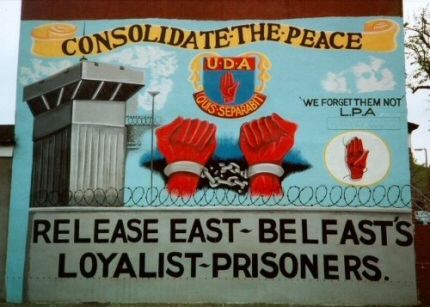

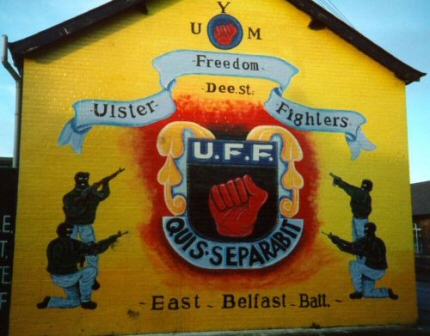

Unionist murals (Loyalist murals, loyal to the UK)

|

|

1. Text: Painting landscapes: the place of murals in the symbolic construction of urban space © Neil Jarman 2006

2. Photos: Mural Directory © Dr Jonathan McCormick 2006