Education in the US

Federal efforts to improve general education

Life in college and university

In

the United States, like in most developed nations in the world, the education

system is divided into two broad levels: general

education(for children below 18) and higher education(for adults

over 18). But the US system differs from those of most other developed nations

in several crucial ways. First of all, the US does not have a national system

of education. Since the

Constitution does not state that education is a

responsibility of the federal government (see

Congress), all educational

matters are left to the individual states. Although there is a federal

Department of Education (it was created only recently, in 1980), its function

is merely to gather statistical data and other information about national

education, to distribute federal educational aid, and to ensure equal access to

education, prohibiting any sort of discrimination (see

![]() ).

Essentially, the control and regulation of education at any level is in the

hands of the states. Each of the 50 state legislatures is free to determine its

own system for its own public schools. Each sets its own requirements for

schools and teachers, and it provides its own funding for public education.

).

Essentially, the control and regulation of education at any level is in the

hands of the states. Each of the 50 state legislatures is free to determine its

own system for its own public schools. Each sets its own requirements for

schools and teachers, and it provides its own funding for public education.

In most cases, however, state constitutions give the actual administrative control of the public schools to the local communities. The local communities elect the school boards, made up of citizens from the local community, which oversee the schools in each district, and their local community taxes largely support the schools. They, not the state, set school policy and actually decide what is to be taught. According to a pithy slogan, education in the US is “a national concern, a state responsibility, and a local function.”

As a result of that, American education is characterized by a great amount of variety and diversity, both in terms of school systems and the content of education. Therefore, it is extremely difficult to describe American education in general terms. Similarly to the criminal justice system, the system of education varies from state to state. Children switch schools at different ages, their schools have different names, and they learn a wide range of different subjects at school in various states. In the following, those features are going to be summarized that are more or less valid for most (if not all) schools in the US.

Attending

school is both a fundamental right of all Americans and a compulsion prescribed

by law. School attendance is compulsory for all children, usually up to the age

of 16. Public education normally begins at age 4 or 5, with kindergarten, which is an

exclusively American term (unknown in Britain, for instance). Kindergarten

consists of one or two preparatory years at school before proper instruction

begins. During this stage there is more emphasis on skills development and

getting children acquainted with community than on formal teaching. After

kindergarten, students enter grade 1(also called first grade) and they normally continue

until grade 12. Most students complete the twelve grades from age

6 to 18, similarly to Hungary. The so-called K-12 system(from kindergarten to grade 12) is free, financed by

the taxpayers’ money in all states. Schools that are part of the K-12 system are

normally called

public schools by

Americans; the term simply means ‘schools open to the public’, in other words,

elementary or secondary schools financed by the state or local government,

where no tuition is required. (Note that the term ‘public school’ has the opposite

meaning in Britain! See

![]() )

)

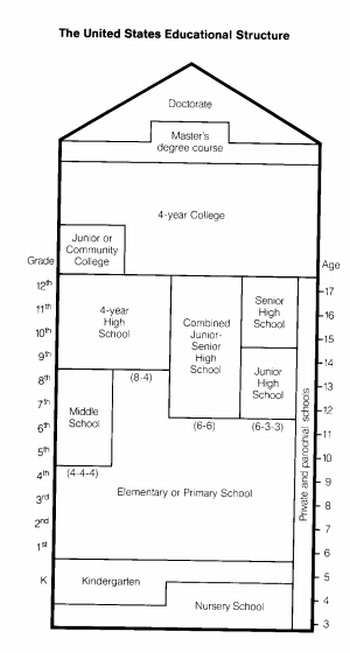

There

is considerable variety, however, in how the 12 grades are divided up between schools

in each state. The lowest level is usually called

elementary schoolin the US, and

it may include grades 1–4 (age 6–10) or grades 1–6 (age 6–12). The next level

may be called middle school in some states or junior high school in others; a

middle schooltypically includes

grades 5–8 (age 11–14), whereas a

junior

high school educates

children in grades 7–9 (age 13–15).

The highest level of the public school system is the

high school, which may take four years after middle school,

grades 9–12 (age 15–18), or three years after junior high school, grades 10–12

(age 16–18). So American high schools are the closest equivalent to a

![]() Hungarian

secondary school (középiskola or gimnázium), but they are not part of

higher education, therefore it is a huge mistake to translate them into

Hungarian as főiskola. The possible combinations of the various kinds of

public schools are illustrated by the following chart:

Hungarian

secondary school (középiskola or gimnázium), but they are not part of

higher education, therefore it is a huge mistake to translate them into

Hungarian as főiskola. The possible combinations of the various kinds of

public schools are illustrated by the following chart:

According to the most recent, 2006 data of the Census Bureau, about 68% (or roughly two-thirds) of all children attend kindergarten in the US, and 88% of all children (that equals 55 million kids) attend one of the more than 95,000 public elementary and high schools in fall 2006. Furthermore, there are also more than 29,000 private primary and secondary schools, which are attended by 12% of the school-age population. As these data show, private schools are not uncommon in the US, but their character is significantly different from the exclusive and often elitist atmosphere of most British independent schools. According to a survey conducted in 2003–2004, over three-fourths (76%) of private schoolsare sectarian schools, founded and maintained by a religious denomination. Catholic schools alone represent 28% of all private schools in the US. Nonsectarian private schools are a relatively small minority (24% of all private schools) in the US, but many of these institutions cater for the children of wealthy parents who wish to educate their kids in a shielded environment with well-paid, well-prepared teachers and a (possibly) stronger educational program. The changing racial proportions of the US (see Race in the US) are clearly reflected in school enrollment: in 2006, as many as 41% of all kids studying in elementary and high schools in the US are non-white or Hispanic, reflecting the growing proportion and the higher birth rate of these groups.

Higher education in the US differs from general education in several crucial ways, but the most important is the necessity to pay large amounts of tuition feein practically all American colleges and universities. A very small number of scholarships (sometimes from local, state and federal governments, but more often from private donors, foundations and charity organizations) is available for exceptionally talented and/or very poor students, and there are special scholarships for talented athletes. Apart from this small minority, however, the great majority of Americans have to finance their own college or university studies. The amount of tuition may range from a few thousand dollars per academic year (in public colleges and universities, which are partly financed by the city or the state they are in, and charge lower tuition fees for local students) to $30–40,000 or more per year in prestigious private colleges and universities. The price of a particular college or university is a crucial factor to consider when students choose a higher educational institution. Otherwise, the choice is enormous: there are more than 4,000 colleges and universities in the US, including public, private, church-related, small and large, two-year and four-year institutions, maintained by cities, counties, and states. Despite the high costs, over 60 percent of all high school graduates enter colleges and universities, because they know very well that a college or university degree is the key to a well-paid job and a successful professional career.

The

two basic types of American higher educational institutions are

collegesand universities.

The term ‘college’ means something very different from Britain where colleges

are typically units within a larger university (e.g. Balliol College within

Oxford University or Trinity College within Cambridge University). In the US, a

college is any higher educational institution which provides a

Bachelor’s degree(the lowest post-secondary degree) to its graduates.

Colleges typically cannot issue higher degrees; issuing

Master’s degreesand

doctorates (PhD)is the privilege of universities. So the American

meaning of ‘college’ is the best equivalent of the

![]() Hungarian concept of főiskola.

Hungarian concept of főiskola.

Many Europeans share the general and obviously prejudiced view that most Americans are ignorant about the rest of the world, and their knowledge is especially limited about European history and culture. This general notion probably contributed to a rather low opinion on the American public education system among Europeans. Lower emphasis on facts and data, and the lack of tough expectations in public schools are often blamed for the perceived ‘ignorance’ of Americans. While there are few entirely objective methods by which the quality of different education systems could be compared, Hungarian secondary school students who studied one or two years in an American institution usually come away with the impression that American high schools are ‘easy’: there are significantly fewer classes per week, the content of the courses is much lighter especially in maths and natural sciences, and they do not have to break their back to score well on tests or satisfy the requirements. At the same time, they usually say that school time in the US is ‘more fun’: the textbooks are carefully structured and easy to understand, teachers are helpful and entertaining, teaching focuses a lot on practice, skills development and individual research, and the lower class load allows students enough time to enjoy extracurricular activities, such as sports, music, creative arts, or many other interests.

Such contrasts between Hungarian and American schools are rooted in fundamental differences in educational philosophy. American general education cannot be simply evaluated as ‘good’ or ‘bad’: it has a variety of goals and corresponding methods which may not match the the goals and methods of the Hungarian general education system.

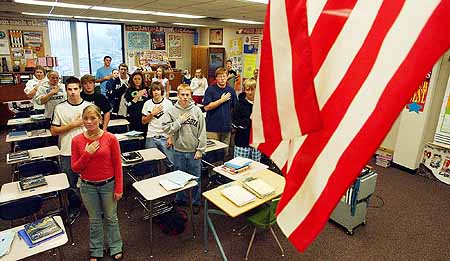

Perhaps the oldest purpose of American public education is to educate republican citizens; in other words, to teach children the basic values of American democracy, and to equip them with such fundamental skills (primarily the ability to read and write) as to enable them to participate in public affairs. Illiterate people cannot read the newspaper and the ballot paper, and most probably do not have enough information and learning to make informed choices at political elections. This argument was a major motivation behind the establishment of free, tax-supported elementary schools in most states.

Pledge taking at a public school |

The second purpose is closely related to the first: free and compulsory public schools have the important task of integrating, “Americanizing” the children of immigrants as well as a wide range of different racial and ethnic groups. In such a radically multi-ethnic and multicultural country, public education has to create a sense of community and identity by emphasizing the bonds that keep the American nation together. This task became especially important in the second half of the 19th century, when large numbers of immigrants arrived in the US from various European countries as well as from East Asia and Latin America (see History of Immigration). These people spoke different languages, followed different faiths, had different cultural backgrounds and histories, which made educators’ task extremely difficult. Thus patriotic education focused on national values and symbols acceptable to all. The universal right of freedom and its defence against tyranny is the central message of the American War of Independence; the Constitution established such democratic principles as an elected government, federalism, and the separation of powers; while the Bill of Rights laid down such individual civil rights as freedom of religion, freedom of speech and press, protection from illegal imprisonment and trial by jury (see The Constitution). These fundamental achievements of the Founding Fathers constitute the heritage of all Americans, regardless of race, nationality or creed. The American flag was chosen as a general symbol of these values, and the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag (composed in 1892) became the most widespread ‘patriotic ritual’ in public schools throughout the US.

The third purpose also follows from the other two: public education should offer equal opportunity to all American children to fulfil their potential, to get a chance for a career and rise in society, regardless of social class, national origin, or racial or ethnic group. This purpose, although it has been present as an ideal ever since the emergence of independent US, remained an illusion rather than reality for a long time. Non-white children, especially segregated blacks, but also Hispanics and Asians, were denied the educational opportunities available for middle-class white kids. After World War II, especially as a result of the civil rights movement, equal opportunity became perhaps the most central issue in American education. The first step towards realizing equal opportunity was the desegregation of public schools in the South, providing access to better schooling for black kids. Despite such legal efforts, however, differences remained huge between various public schools, because they are maintained by local and state taxes. Communities and states that are able or willing to pay more for schools, buildings, materials, and teachers almost always have better educational systems than those that cannot or will not. Rural farming communities and poor inner-city districts have less money available for school buildings, teaching materials, and teacher salaries. More money is spent for the education of a child living in a wealthy district than a child living in a poor community. Just one example: according to the Census Bureau, in 2003–2004, public elementary and secondary school teachers earned an average salary of $57,300 in wealthy Connecticut, while similarly qualified teachers received an average $33,200 in rural North Dakota – barely more than half of the Connecticut salaries.

Federal

and state governments in the past forty years have made various efforts to

reduce differences in educational opportunities. Public policy and legal

decisions have increasingly emphasized special rights for racial, ethnic and

linguistic minorities in the area of education. The federal Bilingual Education

Act was passed in 1968 mostly on the demand of Hispanic organizations, who

protested that Hispanic children perform poorly at school and drop out early

simply because many of them cannot speak English well. The Act as well as subsequent

court decisions ordered that children whose first language is not English must

be offered classes in their mother tongue, be it Spanish, Navajo, or Chinese,

while also taking English language classes. The underlying idea was that in about

three years, students’ proficiency in English should be brought to a level that

is sufficient for continuing their studies in English. According to the Census

Bureau, in 2006 there are about 10 million school-age children in the US

(almost one-fifth of the total) who speak a language other than English at

home. Although more than 7 million of them speak Spanish, the rest is a

colorful mixture of nationalities and languages. As a result, around 80

languages are being used for instruction in American schools, with mixed

results. Supporters of bilingual education argue that by receiving education in

their first language, students’ ability to read and learn in both languages is

improved, while their ethnic identity and self-esteem is boosted (see

![]() ).

Opponents counter that students participating in bilingual education become

fluent in English later, while their educational achievements are often poorer

than those minority kids who studied all subjects in English from the start

(see

).

Opponents counter that students participating in bilingual education become

fluent in English later, while their educational achievements are often poorer

than those minority kids who studied all subjects in English from the start

(see

![]() ).

).

It is also difficult to lessen differences in social background and racial origin by means of education. One attempt adopted in many large cities from the late 1960s was the so-called "busing" of children. This controversial practice wanted to desegregate schools by transporting children by bus not to the school closest to their home, but to another, more distant school, where the ethnic composition of the population was significantly different. For example, many inner-city black children were taken to schools with predominantly white pupils, or vice versa. The goal was to create the same racial proportion of children from various racial or ethnic groups as the one existing in the city’s population overall. Many white parents protested the practice, since they were worried about their children’s safety and the social and criminal problems inner-city blacks import to their schools (e.g. drug abuse, gangs, shootings). In many areas, whites began sending their children to private schools or moved to the suburbs outside city limits. Busing programs were mostly discontinued in the 1980s and 90s, and residential segregation(the spontaneous separation of white and non-white residential neighborhoods) continues to dominate many urban public schools.

In the 1970s, measures to protect minorities from discrimination were extended to both physically and mentally disabled children. Since public schools were ill-equipped to handle their special needs, disabled children had to attend expensive private schools. In 1971, federal courts ruled that public schools should take measures to accommodate disabled children, including the removal of physical obstacles, the employment of special instructors, and installment of specialized equipment where necessary. All this has been achieved in practically all public schools by the 1990s.

As equal opportunity considerations got so much attention in public schools in the past half-century, most public schools have placed less emphasis on tough requirements, since the primary purpose has been to accomodate as many different children as possible, including kids with a non-English mother tongue, disadvantaged social background, or learning disabilities. The relative lack of educational rigor in modern public schools is also partly the outcome of the educational philosophy and methodology developed by John Dewey. Dewey was a powerful critic of 19th century humanistic education (represented mostly by grammar schools), which relied heavily on memorization by rote (mechanical repetition of a word, sentence or piece of information until one automatically remembers it by heart). Dewey argued that such methods kill the joy of learning and do not provide real, usable knowledge since most students do not understand what they are forced to memorize. He proposed alternative methods, such as “learning by doing”, connecting theory and practice (e.g. learning physics while preparing a meal in the kitchen), and giving students individual assignments by which they can utilize their natural curiosity and discover something on their own. Dewey’s theory was based on sharp psychological observations, but many of his followers misunderstood his ideas, and his most lasting legacy remained the relative disregard for ‘dry’ facts and ‘boring’ data.

American

public school

curricula(set of courses and their contents) – as opposed to

![]() Hungarian ones, for instance – have long given up the encyclopedic approach,

that is, the attempt to survey the length and breadth of a given subject.

American students do not study the complete history of the world or the Western

civilisation (but they are usually required to cover the history of the US), they

do not read every major work of American literature, are not given a comprehensive

introduction to physics, chemistry or biology (these subjects are often

combined into a more general Science class), mainly for two reasons. On the one

hand, American educators decided that the time available in general education is

simply not enough to cram all that information into every teenager’s head, therefore

they must be more selective when determining compulsory curricula. On the other

hand, Americans have an entirely different concept of what constitutes ‘useful

knowledge’. They consider it unnecessary for the average person to possess a

wide range of general learning. In order to be decent citizens and useful

members of society, they primarily need practical skills related to their

vocation or career, and they can learn more specialized knowledge in higher

education. Accountants, for example, need good skills in maths for their job but

they can perform their job perfectly well without being familiar with the

theory of relativity or the works of Shakespeare. This practical view of

education, although not shared by all Americans, determines the curricula in

most American public schools.

Hungarian ones, for instance – have long given up the encyclopedic approach,

that is, the attempt to survey the length and breadth of a given subject.

American students do not study the complete history of the world or the Western

civilisation (but they are usually required to cover the history of the US), they

do not read every major work of American literature, are not given a comprehensive

introduction to physics, chemistry or biology (these subjects are often

combined into a more general Science class), mainly for two reasons. On the one

hand, American educators decided that the time available in general education is

simply not enough to cram all that information into every teenager’s head, therefore

they must be more selective when determining compulsory curricula. On the other

hand, Americans have an entirely different concept of what constitutes ‘useful

knowledge’. They consider it unnecessary for the average person to possess a

wide range of general learning. In order to be decent citizens and useful

members of society, they primarily need practical skills related to their

vocation or career, and they can learn more specialized knowledge in higher

education. Accountants, for example, need good skills in maths for their job but

they can perform their job perfectly well without being familiar with the

theory of relativity or the works of Shakespeare. This practical view of

education, although not shared by all Americans, determines the curricula in

most American public schools.

American schools have a relatively narrow ‘core curriculum’ (subjects compulsory for all students). Almost every elementary school instructs children in penmanship (handwriting skills), science, mathematics, music, art, physical education, one foreign language (predominantly Spanish or French), and social studies (a subject combining elements of geography, history, sociology and political studies). Most secondary schools require students to take English, mathematics, science, social studies, and physical education. In addition to this core curriculum, students choose ‘elective courses’ in their areas of interest out of a wide range of possibilities. Computer programming, car design, stage management, or cross-country running are all possible courses in an American public school.

Local control of the schools means that there is a great deal of flexibility both in the core curriculum and in the range of electives. In about two-thirds of the states, local schools are free to choose any teaching materials or textbooks which they think are appropriate. In the remaining states, only such teaching materials may be used in public schools which have been approved by the state boards of education(the equivalent of a department of education in a state). Local school boards often experiment with new programs to meet the community’s wishes and needs.

High school students at the same grade level do not take the same courses. Students who do not plan to go to college may be enrolled in classes such as basic accounting, typing, or agricultural science, which prepares them for vocational or technical positions (vocational education or training is intended to prepare students for a particular trade or profession rather than higher education). Students aiming at college may be enrolled in college-preparatory courses such as chemistry, political science, or advanced writing, more academic subjects required for college work. Talented and ambitious students may take so-called ‘honours classes’ in history, English or science, which are more demanding and cover more material.

What

makes American education at the secondary level different from most other

countries is that all such programs, whether academic, technical, or practical,

are generally taught under one roof. The American high school is therefore best

seen as if it were a combination of all the various types of schools which are

usually separated and kept in separate buildings in other countries.

![]() To use a

Hungarian parallel, an American high school is a Hungarian grammar school (gimnázium) and vocational or technical

school (szakközépiskola, szakiskola)

rolled into one. Although most high school students in America are following

different ‘tracks,’ or courses of study, Americans feel that they should be

kept together as long as possible. They feel that students pursuing different

educational goals should learn together and thereby learn to get along

together. An American high school includes all of the students within the age

group, not just those with the highest academic achievement or interests.

To use a

Hungarian parallel, an American high school is a Hungarian grammar school (gimnázium) and vocational or technical

school (szakközépiskola, szakiskola)

rolled into one. Although most high school students in America are following

different ‘tracks,’ or courses of study, Americans feel that they should be

kept together as long as possible. They feel that students pursuing different

educational goals should learn together and thereby learn to get along

together. An American high school includes all of the students within the age

group, not just those with the highest academic achievement or interests.

In

most American high schools, the

In

most American high schools, the

![]() Hungarian idea of a ‘class’ (a group of 20-30

students who spend most of their school time together, sharing the same classes

and teachers except for a few ‘optional’ classes) is completely unknown. In

American English, a ‘class’ means

(besides a school lesson) all the students belonging to the same grade; they

often talk about ‘the class of 1995’, for example, meaning all those people who

graduated from the school in that year. In an average urban or suburban high

school, such a ‘class’ may include several hundred students. The school day typically

starts at around 8 o’clock every morning and classes often do not finish until

3 or 4 o’clock in the afternoon (this includes the lunch break as well as

music, art, and afternoon sports too). Since each student takes different

classes and follows different tracks, they move from classroom to classroom and

work together with different students each time. As a result, closely-knit

groups similar to

Hungarian idea of a ‘class’ (a group of 20-30

students who spend most of their school time together, sharing the same classes

and teachers except for a few ‘optional’ classes) is completely unknown. In

American English, a ‘class’ means

(besides a school lesson) all the students belonging to the same grade; they

often talk about ‘the class of 1995’, for example, meaning all those people who

graduated from the school in that year. In an average urban or suburban high

school, such a ‘class’ may include several hundred students. The school day typically

starts at around 8 o’clock every morning and classes often do not finish until

3 or 4 o’clock in the afternoon (this includes the lunch break as well as

music, art, and afternoon sports too). Since each student takes different

classes and follows different tracks, they move from classroom to classroom and

work together with different students each time. As a result, closely-knit

groups similar to

![]() Hungarian secondary schools rarely develop in American high

schools; kids have few close friends and a lot more casual pals.

Hungarian secondary schools rarely develop in American high

schools; kids have few close friends and a lot more casual pals.

The weekly schedules usually follow a steady pattern that is easy to remember for kids: for example, they may have the same classes in the same order each day, or courses may be taught in a Monday-Wednesday-Friday or a Tuesday-Thursday rhythm. The length of classes and their arrangements may vary from state to state and from school to school, but a typical class is between 45-55 minutes in length, followed by 5-10 minute breaks. Compared to Hungary, school discipline is often surprisingly strict, especially in urban high schools. Missing classes or being late for classes are considered serious offences and are duly punished. Cheating of any kind is tolerated by neither teachers nor fellow students, who often report cheaters to the teacher; the American view is that cheaters are trying to gain unfair and undeserved advantages over their fellow students, so reporting a cheater is a duty, not morally dubious ‘squealing.’ Schools are protected by security guards who do not allow students in or out of the building during school day. During class time, students are not allowed to loiter on the corridors without the supervision of a teacher or without a written pass. In some inner-city schools, there are metal detectors at the entrance, and students’ lockers are regularly searched in order to find hidden guns or drugs. In such schools with many ‘difficult’ kids, the doors of classrooms are locked during class from the outside, so neither the teacher nor the students may leave until the class is over. Contrary to the popular images suggested by some Hollywood movies, most American students respect their teachers and speak politely to them. On the other hand, they are ready to challenge and argue with their teachers if they feel that their work has been evaluated unfairly, therefore the rules and methods of course evaluation are usually described in detail and in writing at the beginning of each semester.

Course work relies heavily on reading assignments, home essays, individual research projects, and other methods aimed at developing students’ skills to find and select relevant information and turn it into a presentation. Students are encouraged to think critically, give their own opinion on issues and try to justify them with objective arguments. As a result, while American students’ factual knowledge is often inferior to students from other countries, they tend to be more resourceful in handling individual work, more outspoken about their personal views, and more willing to ask questions and criticize established opinions.

Students’ work is commonly evaluated by a scale of 5 grades: the best is A, followed by B, C, and D, which is the lowest pass grade, while F stands for ‘failure’. These grades are often modified by + and – signs, indicating slightly better or worse performances. For instance, a B+ is better than a simple B, but not as good as an A–. Students’ overall academic achievement is measured by their GPA, or ‘grade point average’, where their grades are translated into numbers (A=4, B=3, C=2, D=1, F=0), but honours or advanced placement courses are rewarded with heigher numerical grades, producing a weighted GPA.

Like schools in Britain and other English-speaking countries, schools in the U.S. have also always stressed “character building” or “social skills” through extracurricular activities, including organized sports. There is usually a very broad range of extracurricular activities available. Most schools, for instance, publish their own student newspapers, and some have their own radio stations. Almost all have student orchestras, bands, and choirs, which give public performances. There are theater and drama groups, chess and debating clubs, etc. Students can learn flying, skin-diving, and mountain-climbing. They can act as volunteers in hospitals and homes for the aged and do other public-service work. Sports are especially important, because talented athletes(the word is used for all kind of sportspeople in American English, not just for people doing athletics) are offered full scholarships by colleges and universities. The most popular American college sports are football, baseball, and basketball, but scholarships in soccer (which is a popular sport among women in the US!), volleyball, ice hockey, athletics, tennis, or swimming are also available.

Secondary

education is not finished with any sort of standardized examination like the British

GCSE, the German Abitur or the

![]() Hungarian érettségi: it would be

impossible to introduce any such exam nationwide, since each state is free to

legislate about its own educational system. High school is concluded with a

spectacular

graduation ceremony,

where the graduating class wears long gowns and special, flat-topped caps. Schools

invite a famous and respectable personality (it might be a school alumnus, a

politician, a scholar, or an actor) to give the so-called commencement address

at the ceremony. A chosen student, usually one of the best in the class, also

makes a speech. Students receive a

high

school diploma, which

proves that they have completed their secondary education. Such a diploma in

itself, however, is not enough to gain entry into higher education: they usually

need to take standardized tests for that (see

Higher education).

Hungarian érettségi: it would be

impossible to introduce any such exam nationwide, since each state is free to

legislate about its own educational system. High school is concluded with a

spectacular

graduation ceremony,

where the graduating class wears long gowns and special, flat-topped caps. Schools

invite a famous and respectable personality (it might be a school alumnus, a

politician, a scholar, or an actor) to give the so-called commencement address

at the ceremony. A chosen student, usually one of the best in the class, also

makes a speech. Students receive a

high

school diploma, which

proves that they have completed their secondary education. Such a diploma in

itself, however, is not enough to gain entry into higher education: they usually

need to take standardized tests for that (see

Higher education).

Although

high school graduation is still a traditional occasion for celebration among

family and friends, it is not a very special achievement. According to the

statistics of the federal Department of Education, about 85% of all people aged

25 to 29 have completed high schools, and this figure has been steady since

1976. Although the average dropout rate(the proportion of those students who drop out of

high school before graduation) is low, there are significant differences

between racial groups. Among whites, completion rate is 93%. Among blacks, the

rate has significantly improved since the early 1970s: at that time, less than

60% of blacks finished high school, whereas in 2005 87% of them did. The worst

figures are produced by Hispanics: in 2005, only 63% of Hispanics finished high

school, so they represent the largest group among high-school dropouts.

Federal

efforts to improve general education

Aside from the public schools’ task of socializing and equalizing youngsters of different social, cultural, and economic backgrounds, schools have the obvious job of providing quality instruction. From the 1980s, the American public has become increasingly concerned about the the quality of American public schools as results of standardized tests have shown a continual decline in students’ academic achievement. Researchers have found an alarmingly high level of functional illiteracyamong high-school seniors, especially among minority kids. Maths skills of American students are lagging behind the students of most other developed nations. College freshmen need remedial educationto be able to start standard college courses, because their skills in reading, writing and maths are so poor.

As a result of these findings, the federal government found itself under pressure to get more involved in general education, especially by offering additional funding. The first comprehensive federal educational program was enacted in 1965 under the name Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Its primary aim was to offer federal assistance to poor schools, communities, and children. The original Act was authorized only for five years, so it had to be re-authorized by Congress every few years. New amendments to ESEA began to focus on other goals besides helping disadvantaged schools. The most recent federal assistance program was passed by Congress in 2001, named No Child Left Behind Act.

The Act offered more federal aid to general education than ever before, but under strict conditions. States were required to set up a system to measure the progress of public schools each year. The system may include several elements, such as annual standardized tests for each grade in reading and maths, graduation rates for minority groups, and other indicators. Schools should demonstrate adequate yearly progress to receive federal money; those schools that fail to improve their results for three years are required to reorganize themselves, devise new curricula, fire some of the teaching staff and hire new teachers, etc. Parents whose children attend one of these ‘failing schools’ get the option to transfer their children to another, better school. The Act also set up new, additional requirements for teachers: besides holding at least a Bachelor’s degree, they should pass state qualifying tests in every subject they teach in their school. Schools are required to provide parents with detailed information about the school’s current progress, the quality of teachers, and other facts, in order that parents can make informed decisions about the future of their kids.

The Act was controversial from the start, since it was criticized from many directions. The measurement of the schools’ progress is heavily based on annual testing, but many experts questioned if this is indeed an adequate way to decide whether a school is good or not. Students’ progress depends on their family and social background as much as on their school. Besides, testing can be manipulated too: states are free to introduce any kind of standardized tests, and if the tests are constructed to be very easy, spectacular progress can be produced – on paper. Teachers may be forced to prepare their students specifically to perform well at the tests rather than giving them more comprehensive instruction. Subjects not tested (e.g. history, social studies or art) are threatened with neglect at the expense of reading, writing and maths. Other critics attacked the idea that ‘failing schools’ are threatened with sanctions rather than offered extra help by the federal government. The Act’s emphasis on giving parents the right to remove their children from poorly performing schools also did not meet with universal agreement.

Supporters

of the Act responded by pointing out that the Act finally introduced

accountability into federal financial support: public schools have to produce

results in order to receive federal money. The Act focuses on reading and maths

skills because they are the most fundamental to the student’s further progress.

The performance of disadvantaged groups is closely monitored to make sure that

their lower achievement will not be hidden behind average figures. In general,

the government and its supporters view the Act as a major move towards

improving the overall quality of general education in the US. The success or

failure of this federal effort will only be revealed in the future.

|

View of Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin |

In American English, the term ‘college’ has two meanings. Used in the general sense, it stands for all higher education institutions, including universities. When an American asks you “Have you ever studied in college?”, it would be an entirely wrong answer to say “No, I studied at a university”, because universities are also implied in the question. Similarly, the term 'college degree' may refer to any degree earned in higher education. But used in a specific sense, ‘college’ refers to those institutions which award Bachelor’s degrees to their graduates, but usually cannot issue Master’s degrees or doctorates. A standard college usually takes four years to complete, but there are several other types of colleges (e.g. junior college, community college etc.) which can be finished sooner in return for a lower kind of degree: they usually offer vocational and practical career courses to adult students.

Education at universities is normally divided into two levels or cycles: the undergraduate level (which might even be called a ‘college’ within the university, e.g. Harvard College within Harvard University) and the graduate schools. On the undergraduate level curricula are similar to those of four-year colleges, and students finish their studies with a Bachelor’s degree. Graduate schools are those units of a university that offer specialized and high-quality education to students who have completed a first degree (usually a Bachelor’s Degree) in an undergraduate course. Graduate schools may offer Master’s degreesand doctorates (PhD). Many students move from one institution to another when they have received their first degree, and do their graduate studies somewhere else. There are certain professions that can only be studied on the graduate level, e.g. medicine or law. The graduate schools of a larger university are usually called medical schools, law schools, business schools, etc.

Since World War II, the education system in the United States has been greatly enlarged, educating an ever greater proportion of the population. Much of this expansion took place in higher education. While only about 6 percent of the adult American population (above 25 years) had college degrees in 1950, Census 2000 found that 24 percent of adults possessed college degrees. Since the population of the US increased tremendously in the 20th century, the higher proportion corresponds to even larger numbers: more than 44 million Americans possess a higher education degree, whereas those who have not finished high school are below 36 million. It is worth noting, however, that the proportion of those who studied in a college for some time but dropped out without earning a degree is almost as high as those of college graduates; a total of 21% of the adult population.

The high dropout rate in college may have several causes. Colleges certainly set tougher academic requirements for their students than most high schools; those students who cannot live up to the challenge may soon lose their enthusiasm and give up. Many colleges and universities have a minimum requirement in terms of GPA: those who keep getting poor grades will be forced to leave before graduation. Another common cause of dropping out is money; studying in college is a very expensive thing, since students or their families need to pay five-digit tuition fees each year while also covering the normal costs of living (accomodation, food, clothing, etc.). This is a considerable burden even on wealthy middle-class families; many of them start saving money for their kid’s college tuition right after birth. According to a survey of the Census Bureau, as many as 50% of all full-time college students had a part-time job in 2004 in order to finance their studies. Poor people who cannot afford full-time college tuition may choose to attend two-year institutions (community colleges or junior colleges) part time, which are much cheaper and offer evening and weekend courses. In 2004, 31% of all college students attended two year institutions, and a large part of them were older than 25.

There

are two types of colleges and universities as far as tuition fees are

concerned: the so-called public and private institutions. Public colleges and

universities are not to be confused with the public schools in general

education. These institutions were founded and are maintained by a state or a

city (occasionally by the federal government, as in the case of US military academies):

as a result, they are willing to accept in-state or local students at a reduced

price, but not free of charge. Perhaps the most famous public

university internationally is the

University of California,

which consists of ten different campuses all over the state, including the

world-famous

UC Berkeley

near San Francisco (founded 1868), and

UCLA

in Los Angeles. Under California law, the top 12.5%

of graduating high school seniors have a guaranteed place at one of the UC

campuses, and they pay far less than students coming from outside California.

For instance, the annual tuition fee at Berkeley in the 2006-2007 academic year

is $7800 for undergraduate Californians, but $26,500

for non-residents (see

![]() ).

The average tuition of public institutions nationwide for in-state students was

about $12,600 in 2006 – more than twice as much as in

1990. Public universities typically have city-sized campuses and a huge

undergraduate student body: the University of California (the largest in the

US) educates 159,000 students!

).

The average tuition of public institutions nationwide for in-state students was

about $12,600 in 2006 – more than twice as much as in

1990. Public universities typically have city-sized campuses and a huge

undergraduate student body: the University of California (the largest in the

US) educates 159,000 students!

Private colleges and universities share one common feature: they were founded and are maintained by private individuals or organizations, without the involvement of any governmental entity. Apart from that, private higher educational institutions can be divided into several different categories. Almost all the oldest and most prestigious universities are private, including the Ivy League universities on the East Coast, but also some other famous universities like Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, Duke University in North Carolina, Rice University in Texas, or Stanford University in California. These schools were typically founded by one or more wealthy benefactors as a corporate foundation, and are governed by a board of trustees, similarly to a private company. A special version of these private schools are the so-called liberal arts colleges, which have a relatively small student body (below 5,000), therefore they can offer smaller classes and closer association with professors than large universities. They typically teach humanities, natural and social sciences, and arts, as opposed to more profession-oriented courses (e.g. business, law, medicine, engineering, etc.). Many other schools were founded by religious denominations, and they always include a school of theology or divinity. All the major Protestant churches have a number of colleges and several universities all over the country. The most famous Catholic universities in the US are the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and Georgetown University in Washington D.C.

Private

colleges and universities typically charge a higher tuition fee, since they

have to finance their operation without the help of the state or federal

governments. Their average annual tuition fee was $34,700

in 2006; this figure also more than doubled since 1990. The steep rise of

tuition fees is a cause for concern among students, parents and politicians

alike.

Student loans have long been

available in the US, with conditions similar to Hungary. Students may receive

it from the federal government or from private banks, and they do not have to

pay anything back until 6 to 12 months after they graduated and started working

in a full-time job. Federal student loans are usually more favorable (lower

interest rates, no interest until graduation, etc.), and they are guaranteed by

the federal government (so if the student does not pay it back, the federal

government will pay instead), but they impose a maximum limit on the annual

amount, just like in Hungary. Private loans offer more money on higher

interest. Student who study the longest, especially medical and law students, may

pile up as much as $100,000 or more in debt by the

time they start making money and paying off the debts. Besides the financial

burdens of starting a family and buying a home, college debts can make the start

of an independent career very difficult.

In American higher education, a formal entrance exam to colleges or universities never existed. Since there is no national system of education, students coming from various states and schools display huge differences in their range of knowledge and level of preparation. Therefore, a uniform test on history, physics or any other subject would not evaluate students fairly. The institutions select their students on the basis of written applications, in which they are required to submit a large amount of information about themselves. College officials examine applicants’ high school grades, their outstanding achievements in any field (e.g. in academic competitions, sports or arts), read their essays in which they describe why they want to come to that particular institution. Since World War II, standardized entry tests have played an increasing role in the selection of students. The two most widespread tests are SAT (formerly standing for Scholastic Aptitude Test) and ACT (formerly standing for American College Test). Neither of these tests are prepared by the Department of Education or any other government agency: both tests are developed by private organizations, and colleges and universities are free to decide which test they require from their applicants.

Although

SAT and ACT are slightly different, both focus on evaluating basic skills of

students rather than their knowledge of facts. The SAT Reasoning Test (formerly

called SAT I) currently consists of critical reading, writing, and maths

sections. In the first, students are given passages to read and then they have

to answer questions about them; in the second, they have to compose a short

essay on a given topic; in the third, they have to solve high-school maths problems

by selecting the correct answer out of five options. Results are expressed in a

score: at SAT, 2400 is the best possible score. SAT also offers so-called Subject

Tests (formerly called SAT II), which ask multiple-choice questions on a

certain subject and thus resemble a

![]() Hungarian érettségi exam more closely. Such subject tests are available in

English literature, US and world history, biology, chemistry, physics, advanced

maths, and foreign languages. The majority of colleges and universities, however,

only require SAT Reasoning Tests. ACT includes a Science Reasoning section

besides reading, writing, and maths, and its maths section is supposed to be

slightly more difficult than SAT. The best possible score at ACT is 36.

Although SAT was formerly more popular on the two coasts, and ACT in the

Midwest and the South, nowadays most institutions accept any of the two tests.

Hungarian érettségi exam more closely. Such subject tests are available in

English literature, US and world history, biology, chemistry, physics, advanced

maths, and foreign languages. The majority of colleges and universities, however,

only require SAT Reasoning Tests. ACT includes a Science Reasoning section

besides reading, writing, and maths, and its maths section is supposed to be

slightly more difficult than SAT. The best possible score at ACT is 36.

Although SAT was formerly more popular on the two coasts, and ACT in the

Midwest and the South, nowadays most institutions accept any of the two tests.

When

American students apply to a college or university, they do not have to specify

a subject or, in American English, a ‘major’ they

wish to study at the institution. Most college students start as ‘undeclared

majors’, meaning that they still have not decided what they want to focus on.

This is in sharp contrast with the practice of European higher education, where

students are expected to choose their subject already at the time of

application. The American approach is different for several reasons. Americans

believe that colleges should give students a chance to try their hand at

different courses and make up their mind afterwards, on the basis of their

personal experiences, rather than choosing a major in advance based on little

information or incorrect ideas. Students may wander among majors and satisfy

their curiosity for as long as two years. Also, colleges want to provide a

smooth transition from high school, therefore education in a college at first

is not radically different from a high school. Students still study a wide

range of subjects; all students have to complete some maths, some English, some

academic writing and other general courses, regardless of which major they

choose. Choosing a major simply means that they begin to focus on a specific

area and pick more courses from there, but as much as 30% of their credits comes

from courses unrelated to their major. Another, rarely stated reason behind the

American system is the relatively low level of factual knowledge provided by

most American high schools. Many American colleges are forced to teach general

subjects to their students in order to bring them to a level necessary for the

successful completion of college studies.

The

standard college takes four years to complete. Academic years are divided into

two semesters, similarly to

![]() Hungary, rather than three terms, as in Britain (in American English, the

adjective ‘academic’ simply means ‘related to higher education’ or ‘related to

learning’, while the noun ‘academic’ means a professor in higher education;

neither word has anything to do with any academy as an institution). Students

in each year have their name: first-year students are called freshmen (the term

includes women too), second-year students are sophomores, third-year students are juniors and students

in their fourth and usually final year are called seniors (The same terms are often applied to students of

four-year high schools too). Students are expected to declare their major by

the end of their second year. Double majors (

Hungary, rather than three terms, as in Britain (in American English, the

adjective ‘academic’ simply means ‘related to higher education’ or ‘related to

learning’, while the noun ‘academic’ means a professor in higher education;

neither word has anything to do with any academy as an institution). Students

in each year have their name: first-year students are called freshmen (the term

includes women too), second-year students are sophomores, third-year students are juniors and students

in their fourth and usually final year are called seniors (The same terms are often applied to students of

four-year high schools too). Students are expected to declare their major by

the end of their second year. Double majors (![]() the norm in Hungarian teacher

training colleges and universities until recently) are extremely rare; the more

talented and ambitious students may choose and complete a minor,

which is another study concentration, but students have to complete

significantly fewer courses (e.g. half as many) to finish it. For instance, a

student interested in French history might pursue a major in History and a

minor in French; another one who wants to become a maths teacher may choose

Maths as major with a minor in Education. Each course (including sports and

non-academic subjects) is worth a certain number of credit points,

and all credits are summed up when a degree is issued.

the norm in Hungarian teacher

training colleges and universities until recently) are extremely rare; the more

talented and ambitious students may choose and complete a minor,

which is another study concentration, but students have to complete

significantly fewer courses (e.g. half as many) to finish it. For instance, a

student interested in French history might pursue a major in History and a

minor in French; another one who wants to become a maths teacher may choose

Maths as major with a minor in Education. Each course (including sports and

non-academic subjects) is worth a certain number of credit points,

and all credits are summed up when a degree is issued.

The

workload is not excessively high: an average college student has about 4 to 6

courses in a semester, which is not too bad even if most college courses

consist of two or three classes a week. Institutions usually set a minimum and

a maximum limit on the number of courses allowed in any single semester. American

college courses are more similar to the practical seminars (![]() szeminárium, gyakorlat) than the lecture

courses (

szeminárium, gyakorlat) than the lecture

courses (![]() előadás) of Hungarian

higher education. There are about 15–30 people in a class, and although the

professor does most of the talking, he or she regularly asks questions, invites

students to give their opinion, sets individual or group assignments, etc. Students

are often asked to give a presentation on a specific topic. There are at least

two or three written tests at regular intervals during the semester, but the

előadás) of Hungarian

higher education. There are about 15–30 people in a class, and although the

professor does most of the talking, he or she regularly asks questions, invites

students to give their opinion, sets individual or group assignments, etc. Students

are often asked to give a presentation on a specific topic. There are at least

two or three written tests at regular intervals during the semester, but the

![]() Hungarian ‘examination period’ (vizsgaidőszak)

is completely unknown in US higher education: during the last week of the

semester courses normally end with a final written test, and next week students

go home (usually in mid-December and mid-May). Their grades are mailed to them

by the university. A college program is finished when students have completed

all the compulsory courses of their major plus collected the required amount of

credit points from the electives and the general studies program (courses

unrelated to their major). Writing a thesis or a dissertation is normally not a

prerequisite for an undergraduate degree.

Hungarian ‘examination period’ (vizsgaidőszak)

is completely unknown in US higher education: during the last week of the

semester courses normally end with a final written test, and next week students

go home (usually in mid-December and mid-May). Their grades are mailed to them

by the university. A college program is finished when students have completed

all the compulsory courses of their major plus collected the required amount of

credit points from the electives and the general studies program (courses

unrelated to their major). Writing a thesis or a dissertation is normally not a

prerequisite for an undergraduate degree.

College graduates receive a Bachelor’s degree at the end of their studies. The two most common types of Bachelor’s degree are BA (Bachelor of Arts)and BS or BSc (Bachelor of Science). Students majoring in humanities (e.g. English, History or Philosophy) or social sciences (e.g. Sociology, Political Science) receive a BA, while all other majors are usually awarded with a BSc (e.g. Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Architecture, Engineering, Nursing, etc.). But the division between the two types of degrees is not always so obvious: in some liberal arts colleges, only BAs are issued, regardless of what students are majoring in. At other places, a degree in journalism or education is considered a BS. There are also some specialized degrees, like BFA (Bachelor of Fine Arts) issued to students of art academies, or BM (Bachelor of Music) to students of music conservatories. It is also possible to receive a BE or BEd (Bachelor of Education) in some schools for those planning to become school teachers below high school level.

A college graduate who received his or her degree has two options: to find a job, or to apply to a university graduate school. Some people may work for a few years after college to collect some money, because graduate schools are always more expensive than undergraduate courses. If somebody completed their undergraduate studies at a university, they may choose to stay at the same place and apply to a graduate school there, but this is quite rare except for the best universities. The majority of undergraduates consider it useful to go to another place, to meet new professors, new approaches, new academic environment, as well as getting to know another city or state. Some choose their graduate school specifically because a famous specialist of some field teaches there.

Graduate schools have more formalized entry requirements: they examine students’ grades and choice of courses in college, the recommendations of undergraduate professors, and usually require a test in one or more appropriate subjects (e.g. in Advanced Maths or Physics, or in English and History). Entry to the graduate schools of the most famous universities is very competitive and highly selective: for example, only about 5% of of applicants were accepted by Harvard Medical School, and only 6% by Yale Law School in 2005, and the figures rarely exceed 10% at any Ivy League graduate school. Of course, there are hundreds of other universities where admission is far less difficult.

A graduate program is very different from an undergraduate program, and more similar to a standard Hungarian university program. Graduate students are usually not required to study anything else except courses related to their chosen field. They may not have many courses in one semester, but the requirements are tougher than at the undergraduate level, and usually involve a lot more independent research work. Also, there are one or more comprehensive exams graduate students need to pass in order to continue or complete their studies.

Graduate studies may end with a Master’s degree or a doctoral degree. A Master’s program takes usually one or two years; besides course work, students are expected to submit a Master’s thesisbased on their independent research. The two standard degrees are MA (Master of Arts)and MS or MSc (Master of Science), but due to the more specialized character of graduate programs, there are several more types of Master’s degree available. Graduates of business schools receive an MBA (Master of Business Administration), there is MEng (Master of Engineering) for engineers, MEd (Master of Education) for those specializing on education, MDiv (Master of Divinity) for graduates of theological seminaries, and so on. There are some special Master’s degrees that take considerably longer – three or four years – to complete, primarily law and medicine. The degree of medical graduates is called MD (Medicinae Doctor), and the first degree of law graduates is JD (Juris Doctor) – despite the Latin names, neither of these is a doctorate.

A

doctoral program is usually a direct continuation of a Master’s program, but

takes several more years to finish (usually 5 to 8 years in all). The first two

or three years of a doctoral program mostly consist of advanced courses and are

completed by one or more exams. In some institutions, candidates receive a

transitional title at the end of the first phase, like MPh (Master of

Philosophy) or ABD (all but dissertation). After that, candidates spend several

more years to complete an extensive research project (which may require work at

other institutions or even abroad) and finally, submit and defend their doctoral dissertation. Doctoral

studies are offered primarily to people who want to become college professors,

or pursue some advanced theoretical research in some field. Regardless of the

chosen field, doctoral degrees are nearly always called PhD (Philosophiae Doctor)– this is

received by a candidate in History as well as a in

Chemistry, Engineering or Medicine.

Life

in College and University

Campus of Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX |

Most American colleges and universities are located on so-called campuses, or college grounds. A campus is a large area owned by the college or the university, where the individual buildings are surrounded by a well-tended park. Even small colleges have several academic halls where lecture rooms, classrooms and staff rooms are located; one or more administrative buildings; science laboratories; a library building; a theater or auditorium for stage performances and music concerts; at least one self-service cafeteria, where hot and cold breakfast, lunch and dinner are all available; at least one outdoors stadium for football and baseball; at least one indoors sport center for basketball, volleyball and recreational activities; several residence halls (popularly called dormitoriesor simply dorms) with rooms for students; and some sort of student center, with a bookstore, coffee shops, and other facilities for students who want to hang out. Private colleges and universities almost always have one or more chapels on campus, too (public universities are forbidden to allow any church on campus, since they are financed by a state or city government, which must not support or discriminate in favour of any religious denominations).

Residence halls, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX |

The great advantage of the campus system is that everything is within walking distance, providing an ideal environment for studying, since students find all they need for their day-to-day life and work. Freshmen (first-year) students are usually required to live on campus, in one of the dorms, so that they can integrate into the college community as quickly as possible. Rooms in college dormitories are almost always for two people; Americans are convinced that the roommate system is an effective way to prevent the isolation of individual students. Older students are usually allowed to move off campus, and rent their own room or apartment in town if they wish.

In many American colleges and universities, students have the option to join one of the many student fraternitiesand sororities. These are nationwide organizations with chapters at individual schools, each named by two or three Greek letters, therefore they are collectively called the ‘Greek system’ or the ‘Greeks’. Phi Beta Kappa Society, the oldest such organization, was founded in 1776 as a secret society to honor the most outstanding students at William and Mary College. Later on, other chapters of the society were founded at other universities, so it became a nationwide organization. The various fraternities (which can be all-male or mixed) and sororities (all-female) have different character and goals: some of them want to include the elite of the student body, others require charitable or social work from their members, yet others are primarily interested in socializing and friendship. Fraternities and sororities maintain houses on campus where their members live. Each society has a set of secret rituals modelled on Freemasonic tradition, e.g. initiation, passwords, handshakes, songs, and the like. The initiation rituals, the so-called hazing, have caused occasional scandals, because freshmen are sometimes forced to do degrading and dangerous things (e.g. ritual spanking by older students, performing meaningless tasks, eating and drinking huge amounts etc.), resulting in serious accidents.

Fraternities at Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX |

Higher education was traditionally the privilege of middle- and upper-class white males in the United States until the mid-20th century. Most colleges and universities refused to accept women until the 20th century, whereas poor people, including blacks and other racial and ethnic minorities were effectively excluded by the high tuition fees. This situation has changed tremendously since the 1950s. Following the success of the civil rights movement, public colleges and universities were required by state government to stop segregationist admission policies, while private universities followed suit feeling the pressure of the media and public opinion. Many institutions introduced affirmative action programs, actively trying to recruit more blacks, Hispanics and women, and giving them preferential treatment over white male applicants with similar or even better grades and test points. Such programs, as well as increased assistance by the federal government in the form of grants and subsidized student loans, significantly increased the proportion of women and non-white minorities among college graduates, but also led to controversial public debates and court cases. Many white males protested against preferential treatment of minorities in admission, charging that it amounted to reverse discriminationagainst them. As a result, many such programs were reduced or terminated in the 1980s and 1990s, but the Supreme Court declared in 2003 that race may legally be considered a factor in admission as long as it is not employed in an automatic or mechanical way.

According

to Census 2000, the differences between men and women in educational attainment

have almost disappeared. Men are still at slight advantage but mostly among the

older generations. In 2000, 26% of men had a college degree compared with 23%

of women, and 10% of men possessed an advanced degree (Master’s or doctorate)

as opposed to 8% of women. The gap is wider between whites and blacks: despite

decades of affirmative action programs, only about 14% of blacks have a college

degree and less than 5% can boast an advanced degree. The Hispanics have even

poorer achievements (10% owns a college degree, 4% an advanced degree). At the

other end of the scale stand the Asians who have by far the best educational

attainment among all the racial groups: 44% (almost half!) of them have a

college degree, and more than 14% an advanced degree. This figure shows that

educational achievements cannot be explained simply by poverty, discrimination

or immigrant status; the cultural traditions of individual racial and ethnic

groups (in this case, the ambition to excel and the motivation to work hard for

such a goal) are also a key factor in success.

ACT

affirmative action

athlete

BA (Bachelor of Arts)

Bachelor’s degree

board of education

BS or BSc (Bachelor of Science)

busing

cafeteria

campus

class

college

core curriculum

credit points

curriculum

doctoral dissertation

doctorate (PhD)

dormitory, dorm

dropout rate

elective courses

elementary school

failing school

fraternity

freshman

functional illiteracy

general education

grade 1-12

graduate school

graduation ceremony

hazing

high school

high school diploma

higher education

honours classes

Ivy League

junior

junior high school

K-12 system

kindergarten

MA (Master of Arts)

major

Master’s Degree

Master’s thesis

middle school

minor

MS or MSc (Master of Science)

PhD (Philosophiae Doctor, doctorate)

preferential treatment

private school

public schools

remedial education

residential segregation

reverse discrimination

roommate system

SAT

school board

sectarian school

semester

senior

sophomore

sorority

Student loan

tuition fee

undergraduate level

university

vocational education

Sources:

Educational

Attainment: 2000. Census 2000 Brief.

![]()

Statistical

Abstract of the United States 2001. Section 4: Education

![]()

Census Bureau Press Releases: Facts for

Features: Back to School 2006-2007

![]()

Douglas K. Stevenson, American Life and Institutions. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett, 1996.

Wikipedia the Free Encyclopedia