·

To harmonize

two conflicting requirements: the essential equality of the member states and

the democratic representation of the people of the US.

·

To prevent the

development of a tyrannical, all-powerful central government by limiting both

the scope of authority of the central government and the individual branches of

power within it.

These objectives were often in contradiction,

therefore the ultimate framework of the

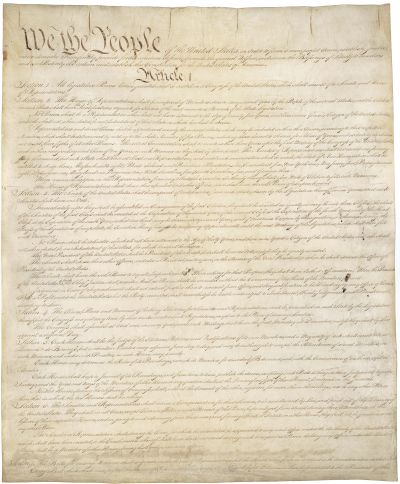

Constitution has

been produced by a series of compromises. The two key principles determining

the present shape of the Constitution are the

separation

of powers and

federalism.

Separation

of powers means that the federal government is divided into three

separate branches – the legislative,

the executive and the judicial – each of which is represented

by a specific institution. The three

branches of power are separated from one another, which means that the

members of each branch gain their position separately and exercise their

authority independently. Nobody is allowed to be a member of any two branches

of power at the same time. This way, the Founding Fathers wanted to make sure

that none of the three branches can concentrate too much power in their hands

and suppress the other two. They even included a special system of

checks and balances (rules by

which one branch can control and limit the power of another) into the

Constitution as a further protection ’against tyranny’.

Federalism means that the federal government shares political

power with state governments. Both the federal government and the various

states have their own specific functions and authorities, which should be

mutually respected. Therefore the

Constitution made a

clear distinction between federal and state powers by specifying what powers

belong to the federal government.

Each of the three branches of power is represented

by one institution:

Congress is the

legislative body, the

President

exercises all executive powers, and the

Supreme

Court is the highest judicial authority. Congress consists of

two houses (also called a bicameral

legislature): the lower house is called House of Representatives, and the upper house is called Senate.

Both houses are elected, but in a different way and for different periods of

time (see Congress). The President is elected independently from

Congress.

The legislative and the executive branches are forced to cooperate in order to

govern the country: the President cannot force Congress to pass legislation they do not want to; on the

other hand, he has the right to veto

bills of Congress he disagrees with. The President can exercise executive power

with a great amount of liberty, but all his major appointments and his most

crucial decisions (e.g. declaration of war) must be approved by Congress. All

these limitations are parts of checks and balances.

Members of the Supreme Court are chosen in a

cooperation of Congress and the President, but once they are appointed, they

remain there for the rest of their life or until they wish to retire. The

Constitution described the powers and authority of the Supreme

Court in a lot less detailed way than those of Congress and the President; most

importantly, it is not specified in the

Constitution how

the Supreme Court can check and balance the other two branches of power.

Subsequently, such a power was created by the Court itself, in the form of

judicial review (see Supreme Court).

Besides describing the three branches of powers and

their scope of authority, the Constitution also

provided a way to change or modify its own content. It allowed Congress with a

two-thirds majority, or two-thirds of the states, to propose so-called amendments (modifying clauses) to the

Constitution. Each of these amendments must be ratified

(accepted) by three-fourth of all states in order to become part of the

Constitution. This way, the Founding Fathers made it possible

for subsequent generations to modernize the

Constitution and

harmonize it with future political and social necessities.

Soon after the

Constitution itself

was ratified in 1788 and the first Congress convened in 1789, ten amendments

were passed by Congress and ratified by enough of the states by 1791. These ten

amendments, collectively called Bill of Rights, contained those individual rights

of the citizens of the US which must not be taken away or offended by either

the federal or the state governments. Although the Bill of Rights was passed

slightly later than the original

Constitution, it

was so close in time that most people consider it part of the original text.

Since then, the

Constitution has

been amended 17 more times, so altogether there are currently 27 Amendments to

the Constitution. One of them, however, is no

longer valid: the 18th Amendment, which was passed in

1919 and made the production and sale of alcoholic drinks illegal in the US,

was repealed in 1933.

Congress represents one of the three branches of power in

the federal government of the United States. The rules governing the election

and operation of Congress are contained in Article I of the US

Constitution. Congress occupies the huge and impressive

building of the

Capitol in Washington D.C. Since the

building stands on a small hill, journalists and commentators often refer to

Congress as ’Capitol Hill’.

The Capitol |

Congress possesses all legislative powers in the federal

government. It consists of two legislative houses: the lower house is

called House of Representatives, and

the upper house is called Senate.

Each house has a different representative function: the Founding Fathers

imagined the House of Representatives to represent the people of the US, while

the Senate was meant to represent the member states in the federal legislature

(that is, two Senators for each state, no matter the population of the state;

thus there are now 100 Senators representing 50 states).

The members of the House of Representatives

(

)

― who

are simply called Representatives

― are elected by the citizens of the US. The territory of each state is divided

into Congressional districts with

roughly equal number of voters, and each district elects one Representative

into the House every two years. Each Representative must be at least 25 years

old and must live in the state in which he or she has been elected.

)

― who

are simply called Representatives

― are elected by the citizens of the US. The territory of each state is divided

into Congressional districts with

roughly equal number of voters, and each district elects one Representative

into the House every two years. Each Representative must be at least 25 years

old and must live in the state in which he or she has been elected.

In the early 20th century, the total number of

Representatives in the House was fixed at 435. Since the population of the US

is continuously growing, and some states attract far more people than others,

the fair and equal distribution of Representatives among the states must be

regularly maintained. Every ten years, following a national census (counting of the population),

the number of Representatives is reapportioned

(redistributed) among the states to reflect the changes in their population.

California, the most populous state, currently has 53 Representatives, but even

the smallest states must have at least one, regardless of how small their

population is. Currently, there are seven states with only one Representative

in Congress. The latest apportionment

was made after the 2000 Census: on the basis of that, each member of the House

represents about 650,000 Americans. (For the details of federal elections, see

Elections)

The members of the Senate (

)

― who are called Senators

― are nowadays also elected by the voters of the state they represent, but this

has not always been the normal way. The logic of the Founding Fathers was that

the Senate represents the states of the US, therefore Senators should be chosen

by the legislature of the state they

will represent. This remained the general practice during the 19th century, but

the 17th Amendment in 1913 made the popular

election of Senators compulsory in all the states. Nonetheless, the most

important principle remained the same: in the Senate, all states are equal,

because each state has two Senators, elected for six years. Both Senators are

elected by all the voters of the state, but always in a different election

year. Senators must be at least 30 years old and must live in the state they

represent in the Senate.

)

― who are called Senators

― are nowadays also elected by the voters of the state they represent, but this

has not always been the normal way. The logic of the Founding Fathers was that

the Senate represents the states of the US, therefore Senators should be chosen

by the legislature of the state they

will represent. This remained the general practice during the 19th century, but

the 17th Amendment in 1913 made the popular

election of Senators compulsory in all the states. Nonetheless, the most

important principle remained the same: in the Senate, all states are equal,

because each state has two Senators, elected for six years. Both Senators are

elected by all the voters of the state, but always in a different election

year. Senators must be at least 30 years old and must live in the state they

represent in the Senate.

The two houses of Congress are equal in legislative

power: both of them must approve all bills

before they can be sent to the President for signature. They have different

roles in the impeachment procedure

(see President). There are a few signs, however, indicating that the

Founding Fathers wished to give the Senate slightly more power and influence

than the House. For instance, the Senate was given the power to approve the

appointments made or foreign treaties signed by the President, while the House

has nothing to do with them. Also, Senators are elected for long terms (six

years, compared to two-year terms for Representatives) and usually by a much

larger number of voters, which gives them more prestige and respect. Many

experienced Senators are well-known politicians nationwide, while few

Representatives are recognized outside their state or even their district.

Nonetheless, the lower house does have a significant privilege: all revenue

bills must originate in the House of Representatives.

The legislative powers of Congress are not

unlimited: the Constitution specifies a number of areas where Congress has the

power to make laws. Such areas include:

·

Finance and

trade: Congress can coin money and

determine its value, borrow money for the purposes of the state, impose uniform

taxes and duties all over the US, regulate commerce both inside the country and

with other nations.

·

Citizenship: Congress can determine the rules of

naturalization (how someone can become

a citizen of the US)

·

Communication: Congress maintains the postal service and can

build post roads. (Of course, today it includes all other forms of

communication too)

·

Economy: Congress can determine bankruptcy laws and

protect the interest of inventors and authors (patent and copyright laws).

·

Defense: Congress can declare war, set up and maintain an

army, a navy and a militia (volunteer armed force to protect against internal

unrest and riots; today it is called the National Guard).

·

Government

of federal lands: Congress has exclusive legislative control over

the federal capital (Washington D.C.) and any other federal land that does not

belong to any states.

The Constitution left

it unclear whether Congress may pass laws regarding other areas not specified

by the text. In the 19th century, the

Constitution was

typically interpreted in a restricted way, which means that Congress can only

make law in those areas listed by the

Constitution. In

the 20th century, a looser interpretation gained ground, which construed

the areas above as examples rather than an exclusive list. As a result,

Congress has gained a lot of power at the expense of the state legislatures

during the past two centuries.

The White House |

The President represents one of the three branches

of power in the federal government of the United States. The rules governing

the election and functions of the President are contained in Article II of the

US Constitution. The official residence of the

President is the

White House

(

) in Washington D.C.

) in Washington D.C.

The President possesses all executive powers in the

federal government. He is the only person in the government to be elected by

the entire nation, therefore his prestige and respect are unique in the US. He

is elected for four years together with a

Vice-President

(

),

who steps in his place if the President dies, resigns, is removed from office

or becomes unable to exercise his duties. He must be at least 35 years old and

a born citizen of the United States.

),

who steps in his place if the President dies, resigns, is removed from office

or becomes unable to exercise his duties. He must be at least 35 years old and

a born citizen of the United States.

Compared to European parliamentary systems of

government, the President combines two distinct functions: he is both the head

of state and the head of the government of the United States; the President may

be compared to the British

monarch and the Prime Minister, or the Hungarian President of the Republic and

the Prime Minister rolled into one very powerful person. As a result, he

has a wide range of powers, which could be categorized as follows:

·

As head of

state, the President has the exclusive right to turn bills of Congress into law, or

Acts

of Congress. The Constitution gives him

veto power over bills of Congress, that

is, he may refuse to sign any bill he does not like (such a wide power is not

possessed by either the British monarch or the Hungarian President). The

President has ten days to decide whether to sign or veto; if he does not act at

all, the bill automatically becomes law, without the President’s approval. If

he vetoes, Congress may override his

veto by passing the same bill again with two-thirds majority in both

houses. In such a case, the President can no longer prevent the bill from

becoming law, but during US history, only in about 4% of veto cases was

Congress able to override the veto by collecting the two-thirds majority behind

the bill.

·

Also as head

of state, the President appoints all major federal officials, including all

federal judges, all the members of the President’s Cabinet, all foreign

ambassadors, all the directors of federal agencies and other organizations,

etc. In parliamentary systems, such appointments are formally made by the

monarch or the president, but the actual persons are chosen and recommended by

the Prime Minister. The US President both chooses his candidates for the

various positions and appoints them, with one single limitation: his

appointments must be approved by the majority of the Senate.

·

Also as head

of state, the President exercises a number of less significant powers: he can

give pardons for federal offenses, receives foreign ambassadors, convenes Congress

for special sessions, etc.

·

As chief executive officer, that is, the

head of the US government, the President is responsible for enforcing the laws

of Congress. In practice, he governs the country with the help of 14

executive departments, which are led by

Secretaries. These Secretaries form the President’s

Cabinet, which the President usually consults before making

important decisions. Contrary to the Cabinets of European countries, however,

the President is not obliged by law to hold regular Cabinet meetings or discuss

any issues with his Secretaries; he has the right to make all decisions on his

own if he wishes (see Executive Departments for more details).

·

Besides the

executive departments, the modern President is the head of an enormous federal

bureaucracy, which mostly developed during the 20th century. The White House

Office (also called

Executive Office) includes hundreds of personal assistants and other staff members,

officially led by the

Chief of Staff.

There is also a large number of

federal

agencies, employing millions of people nationwide. The steady growth of

bureaucracy is constantly criticized by political scientists, journalists and

the general public alike, since the bureaucracy tends to isolate the President from the

outside world, slow down planning and decision making and usually resists any

reforms that would threaten the bureaucrats' influence.

·

The President

is the commander-in-chief of all the

armed forces of the US, and he appoints all the generals of the armed forces.

While in most parliamentary systems the head of state is formally

commander-in-chief but the actual direction of the army belongs to the Prime

Minister, the President has the exclusive right to issue commands and orders to

the US armed forces, especially during wartime.

From the list above it seems that the President is

a uniquely powerful figure among the political leaders of Western democracies.

This is probably true in theory but not necessarily true in practice. Despite

his wide range of authority, the President also has to face strong limitations

to his power, created by the principle of the separation

of powers in the Constitution.

In European parliamentary systems, the informal

influence of Prime Ministers is much larger than their formal powers, since

they are almost always the leader of the party or the coalition of parties that

commands a majority in Parliament. As a result, they can reasonably expect MPs

to support bills or other motions proposed by the government; at times they can

even exercise pressure on the majority party to line up behind the government. This

way, a Prime Minister is able to carry out his political program and get the

necessary bills passed by Parliament.

The relationship between the President and Congress

is entirely different. Due to the separation

of powers, the President is elected independently from Congress, and

has no institutional connection to any of the two houses. The President has the

right to propose bills to Congress, but cannot force Congress to pass them,

just as Congress cannot force the President to sign bills passed by them. This

practical independence and equality is a serious limitation on the

President’s power as chief executive. It often happens that the President

belongs to one party, while the other party has a majority in one or both

houses of Congress, and if the majority is hostile to the President, he is

practically unable to carry out any consistent political program. But even if

the majority of Congress' members are from the same party as the President, there is no

guarantee that they will unconditionally support his initiatives: he often has

to try and persuade influential Congressmen informally to get their support for

his purposes. The legislative and the executive branches are carefully balanced against

each other, and if they want to achieve anything, they are forced to cooperate

as equals.

A very radical and rarely used weapon of Congress

against the President is

impeachment.

Impeachment is a legal procedure against the President which can be initiated

if he is suspected to have committed something illegal. It is not a criminal

trial in the normal sense, because it is not conducted by the judicial branch

but by Congress: the House of Representatives has the exclusive right to

initiate impeachment by majority vote, while the Senate has the exclusive right

to hold impeachment hearings and ultimately, to convict or acquit the

President. The impeachment procedure is led by the Chief Justice of the Supreme

Court, while the whole of the Senate acts as a huge jury. In the end, at least

two-thirds of Senators must vote against the President to convict him.

Impeachment is the only legal way to remove an active President from office.

Besides removal, there is no other penalty, but once the President has been

removed, he can be brought to trial in a standard criminal court, because he is

no longer protected by the immunity of his office.

In the history of the US, only two presidents have

been impeached: Andrew Johnson in

1868, and Bill Clinton in

1998. In both cases, the procedure was more about politics than any criminal

activities: President Johnson strongly opposed the Reconstruction program of Congress, while

President Clinton tried to hush up his extramarital affair with a young female

assistant, and the Republican-dominated Congress impeached him for perjury (false testimony before court)

in order to ruin him politically. Both presidents were acquitted, because there

was no two-thirds majority in the Senate to convict them (although in the case of

Johnson only one vote was missing). Contrary to popular belief, President Richard Nixon was not impeached in 1973

after the Watergate scandal: he resigned from office before impeachment could

have been initiated against him – the only American President ever to do so.

The Constitution created

an unusual system for electing the President of the US: he is

not elected directly by the people, but by the so-called electors. The Founding Fathers probably invented the

electoral college (the widespread name

for the collective body of electors) because they did not entirely trust the

people to make a wise choice in such an important question (see

Creation of the Constitution).

In practice, however, the voters of each state decide which candidate should be

supported by their state’s electors. (For details, see

Federal Elections).

The original

Constitution did

not limit the number of times a President can be re-elected. The first

President of the US,

George Washington,

however, decided to step down when his second term in office ended, and he

created a strong precedent: it became a tradition that all later Presidents

retired once they had spent eight years in office. The only President who broke

this tradition was Franklin D. Roosevelt,

who decided to run for a third time in 1940, arguing that the dangerous

international situation (World War II had

broken out in Europe) required a strong and experienced national

leader. He was re-elected once more, in 1944, but died the next year. In order

to prevent such an event in the future, the

22nd Amendment was

ratified in 1951, and since then, nobody can be elected President more than

twice.

Examining the personal background and former career

of past presidents, one can see that all former Presidents have been white

males, and all of them belonged to one of the many Protestant denominations

except for John F. Kennedy,

the only Catholic President in American history. So far, neither women nor

nonwhite politicians have ever been elected President or Vice-President (the

Democrats had a female vice-presidential candidate in 1984, but they lost the

election). Most Presidents had been prominent politicians – Vice Presidents,

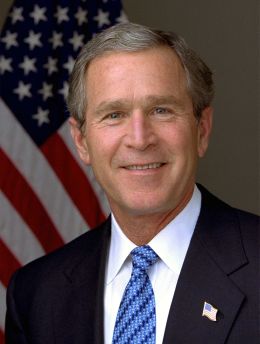

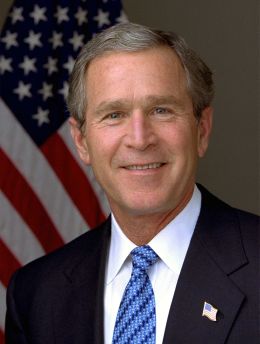

Senators, or state governors – before they won the presidency. For example, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton, the two most recent

presidents, had been governors of Texas and Arkansas, respectively. The typical

exceptions to this rule are former generals or military heroes, who have a good

chance of being elected. George Washington led the American

Revolutionary army during the War of Independence; Ulysses Grant, who was president in the

1870s, had become famous as the commander of the Northern troops during the

Civil War. The last person who won the presidency without a former political

career was Dwight D. Eisenhower

in 1952, who had been the Supreme Commander of Allied troops in Europe during

World War II.

The

executive departments in the United States are the equivalents of European ministries

( Hungarians should be careful not to use the terms

'minister' and 'ministry' for US departments and their leaders, because these

words have an exclusively religious meaning in American English; see

Religion in the US). Each department is headed by a Secretary,

who is chosen and appointed by the President. Currently (since 2002), there are

fifteen executive departments, whose Secretaries constitute the President’s

Cabinet. The oldest and most important departments are the following:

Hungarians should be careful not to use the terms

'minister' and 'ministry' for US departments and their leaders, because these

words have an exclusively religious meaning in American English; see

Religion in the US). Each department is headed by a Secretary,

who is chosen and appointed by the President. Currently (since 2002), there are

fifteen executive departments, whose Secretaries constitute the President’s

Cabinet. The oldest and most important departments are the following:

·

The Department of State (also called State Department), headed by the Secretary of State. Although its name

does not reveal it, it is responsible primarily for foreign policy and the

diplomatic relations of the US with other countries, so it is the equivalent of

the British Foreign Office, or

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hungary.

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hungary.

·

The Department of the Treasury, headed by the Secretary of the Treasury. It is the equivalent of the Exchequer in

Britain, or

the Finance Ministry in Hungary. It is responsible for the

financial affairs of the federal government, including the federal budget, the national

debt, the collection of taxes and duties. It also supervises banks and

financial institutions nationwide, and advises the government on general

economic policy. Besides these responsibilities, it performs some of the

functions of a national bank in Europe, for example it oversees the issue of

coins and paper money. Perhaps the most respected and feared bureau of the

Treasury is the

Internal Revenue Service

(IRS), responsible for collecting all sorts of taxes, and also investigating tax evasion (the equivalent of

the Finance Ministry in Hungary. It is responsible for the

financial affairs of the federal government, including the federal budget, the national

debt, the collection of taxes and duties. It also supervises banks and

financial institutions nationwide, and advises the government on general

economic policy. Besides these responsibilities, it performs some of the

functions of a national bank in Europe, for example it oversees the issue of

coins and paper money. Perhaps the most respected and feared bureau of the

Treasury is the

Internal Revenue Service

(IRS), responsible for collecting all sorts of taxes, and also investigating tax evasion (the equivalent of

APEH

in Hungary).

APEH

in Hungary).

The Pentagon |

·

The Department of Defense

(also called Defense Department), headed by the Secretary of Defense. As the name suggests, it is responsible for

overseeing the US armed forces and conducting military operations. The

headquarters of the Defense Department is the famous

Pentagon building in Washington D.C. The three major divisions of

the US armed forces are the

Army, the

Navy

and the

Air Force. The

Marines,

special units which can be rapidly deployed in foreign countries, belong under

the Navy. The National Guard & Reserve

unites all former military people who are ready to take up active duty if

necessary. The highest ranking military officer overseeing all strategic

military planning and operations is the Chairman

of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff. He is directly responsible to the Defense

Secretary and to the President.

·

The Department of Justice (also called Justice Department), headed by the Attorney General. It is responsible for

representing the federal government in legal suits and cases, prosecuting

federal crimes, and advising the President on legal issues. The Department

supervises all federal law enforcement agencies, including the famous FBI (see

below).

These four departments or their predecessors have

existed since 1789, so they constitute the core of the executive branch. The

other departments are more recent (mostly 20th century creations), and they

mostly deal with less crucial issues and therefore their leaders are less

influential and not widely known politicians. Also, their authority overlaps

with those of the state governments, so they often have limited influence over

the day-to-day operation of their area. These departments are:

·

Interior,

Agriculture, Commerce, Labor, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban

Development, Transportation, Energy, Education, Veteran Affairs, and Homeland

Security.

Perhaps the most powerful of these is the most

recent department, the

Department of Homeland Security,

created in 2002 after the terror attacks on September 11

2001 to oversee and coordinate all federal government efforts

against terrorist activities on American soil. The Department received a wide

range of powers and functions. It took over from the State Department the

naturalization (granting of US

citizenship) of foreigners and the issue of

green cards (permanent residency permits). It supervises all

bureaus and agencies responsible for customs and border control as well as

guarding the coasts of the country. It enforces immigration laws by prosecuting

and expelling illegal immigrants. It

is also responsible for organizing government response to major emergencies

like natural disasters.

Besides the executive departments, there are

numerous federal agencies, which are one step below in the organizational

hierarchy, but in fact some of them are more influential than many of the

departments. Some of the most important and most widely known are:

·

Federal Reserve System (also called Fed): The organization responsible

for the monetary policies of the US, for example the inflation rate and the

interest rate of the US dollar. It is independent from the federal government,

overseen by its own Board of Directors appointed by the President. It is

roughly the equivalent of a central or national bank of European countries,

although it shares some of these functions with the Treasury.

·

Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI):

Federal law enforcement organization, which investigates federal crimes (crimes

that do not belong under any particular state’s criminal justice system).

People working for the FBI are not called ’police officers’ but ’federal

agents’.

·

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA): The organization responsible for collecting

and analyzing information about other countries, especially from the point of

view of US national security.

·

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): The organization overseeing US space

research programs.

·

The Postal Service

(USPS): It is the oldest federal service, today

less important than it was before the invention of electric and electronic

communication devices, but it is still under the direct authority of the

President.

Besides these high-profile organizations, there are

many other agencies which are less well-known but their work is crucial, such

as the Environmental Protection Agency, the Federal Communications Commission,

the Commission on Civil Rights, and many others.

The Supreme Court

|

The Supreme Court

building |

The Supreme Court represents one of the three branches of power in the federal government of the United

States. The main

functions of the Supreme Court are briefly described in

Article III of the US

Constitution, while the

appointment of its members is contained in Article II. The building of the

Supreme Court is located in Washington

DC.

The Supreme Court

is the highest judicial body in the US, and its legal decisions are final, they can only be

changed or modified by the Court itself. The members of the Court are called Justices: the Court is led by the

Chief Justice, and there are (since

1869) eight Associate Justices. Each

Justice is appointed by the President, but the majority of the Senate must

confirm the appointment. Justices may remain in their position during

"good behaviour" according to the

Constitution, which is

understood as lifelong terms or service until voluntary retirement. Justices cannot be

removed from the Court except by

impeachment

(for the rules of impeachment, see the President). When a

Justice dies or retires, the current President has the opportunity to appoint a

new member.

Procedure of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court today unites two different functions: it is the highest

court of appeal in the US, while it also has the final right to interpret the

Constitution. These two

functions are separated in many European countries:

in Hungary, for example, the first task is performed by the

Hungarian Supreme Court (Legfelső Bíróság), while the second is the

responsibility of the Hungarian Constitutional Court (Alkotmánybíróság).

The Constitutional

Court is

separated from the regular court system of the country: any citizen or

organizaton may turn to the Constitutional Court with any question or problem which involves the correct application of

the country’s constitution. The President of the Republic can also turn to the

Court if he has doubts about the constitutionality of an Act of Parliament he

is expected to sign.

in Hungary, for example, the first task is performed by the

Hungarian Supreme Court (Legfelső Bíróság), while the second is the

responsibility of the Hungarian Constitutional Court (Alkotmánybíróság).

The Constitutional

Court is

separated from the regular court system of the country: any citizen or

organizaton may turn to the Constitutional Court with any question or problem which involves the correct application of

the country’s constitution. The President of the Republic can also turn to the

Court if he has doubts about the constitutionality of an Act of Parliament he

is expected to sign.

This is very different in the US: the

Constitution limits the Supreme Court to dealing with "cases

and controversies". Therefore, the Court does not give general opinions in

response to people’s petitions, does not review laws before they are signed by

the President, and does not advise anybody on possible constitutional problems.

Its function is limited only to deciding specific cases. In practice, it means

that a constitutional problem can only be raised by a person whose

constitutional rights are directly injured by the law or rule. For example,

in

Hungary the Constitutional Court declared capital punishment

unconstitutional in 1990 after an ordinary citizen’s petition. In the US, only a person sentenced to death could appeal to the

Supreme Court questioning the constitutionality of the capital punishment.

(Actually, there have been such appeals and the Court has decided that capital

punishment is not against the

Constitution as long as it is performed without cruelty and

bias; see Landmark cases

below).

in

Hungary the Constitutional Court declared capital punishment

unconstitutional in 1990 after an ordinary citizen’s petition. In the US, only a person sentenced to death could appeal to the

Supreme Court questioning the constitutionality of the capital punishment.

(Actually, there have been such appeals and the Court has decided that capital

punishment is not against the

Constitution as long as it is performed without cruelty and

bias; see Landmark cases

below).

The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction in a very small number of

cases arising out of disputes between states or between a state and the federal

government. Apart from these, most cases reach the Supreme Court through

appeals from lower courts. The Court receives about 8,000 criminal and civil

cases from lower federal as well as state supreme courts in one term, which

lasts from one October to the next. Each case is assigned to a Justice who

decides whether it merits examination by the Court. Plenary review, with oral

arguments by attorneys, is held in about 100 cases per term. This means that

the whole Court gathers and listens to the arguments of the two lawyers

representing the two opposing sides of the case (in constitutional cases, the

defendant or the plaintiff is often the federal government or a state

government). Justices also ask both attorneys various questions. Then they

retire to discuss the case, and either come to a unanimous decision, or take a

vote. Since there are nine judges, there must be at least a 5-4 majority in

favour of one opinion. Then one of the Justices is asked to write a formal

written opinion in which he or she explains the reasons and the exact meaning

of the decision. Justices who disagree with the decision of the majority may

write dissenting opinions in which

they explain why they refused to agree and why they think the decision is

wrong. Both the majority and the minority opinions are published and are

available for all. Approximately 50–60 additional cases are taken care of

without plenary review. The publication of a term’s written opinions and orders

approaches 5,000 pages. (For details on how the Supreme Court works, see

;

for a collection of significant oral arguments between 1955 – 1993, see

;

for a collection of significant oral arguments between 1955 – 1993, see

)

)

When the Supreme Court rules on a constitutional issue, that judgment is

virtually final; its decisions can be altered only by a new amendment to the

Constitution (which is

very difficult to create, because it must be approved by two-thirds of both

houses of Congress as well as ratified by three-fourths of all the states) or by

a new ruling of the Court. However, when the Court declares a law

unconstitutional, the state legislature or the federal Congress may pass a new

law to eliminate the constitutional problem.

Although the Supreme Court has been established by the

Constitution along with

Congress

and the President, its functions and powers are defined much more

briefly and far less precisely than those of the other two branches. It is

difficult to tell today why the Founding Fathers devoted so much less

attention to the Supreme Court than to the other two branches of power. In

accordance with the principle of the separation

of powers, they obviously wanted

to guarantee the independence of the judicial branch. The other two branches

have limited control over the Supreme Court: the President can influence the

Court by the selection of new Justices (although the Senate may reject his

nominee), while Congress can pass an Act which changes the number of Justices

or the system of lower federal courts.

But apart from these, the Supreme Court is protected from interference of the

other two branches.

The Constitution itself, however, gave no explicit authority to the Court to exercise any

kind of control over the other two branches of power. In this respect, the

Founding Fathers either made a mistake or a deliberate omission, because

they left the checks and balances system incomplete. It was

the Supreme Court itself which corrected the error in 1803: in the case

Marbury v. Madison, the Court

declared its exclusive right to

judicial review,

or the right to examine laws of Congress and determine whether they are in

accordance with the Constitution. If not, the Court reserved the right to declare

such laws void. Although the

Constitution never explicitly gave the power of judicial

review to the Supreme Court, it has become part of the constitutional

tradition, and as a result, the Supreme Court has become the guardian and

interpreter of the Constitution.

The Court’s opinion in Marbury v.

Madison was written by Chief Justice John Marshall, perhaps the most important person in the history of the

institution. Marshall remained on the Court for more than 34 years, from 1801

to 1835, and his vigorous and able leadership in the formative years of the

Court was central to the development of its prominent role in American

government. In the Marbury decision,

the Chief Justice asserted that the Supreme Court's responsibility to overturn

unconstitutional legislation was a necessary consequence of its sworn duty to

uphold the Constitution. That oath could not be fulfilled any other way. It is the task of the

judicial branch to say what the law is. With his opinion, he clarifed that the

interpretation of the Constitution is necessary and it must be performed by the

Supreme Court. The Founding Fathers had wisely worded that document in rather

general terms leaving it open to future elaboration to meet changing

conditions. John Marshall expressed the challenge which the Supreme Court faces

in the following way: "We must never forget that it is a constitution we

are expounding ... intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently, to be

adapted to the various crises of human affairs."

The Supreme Court first assembled on February 1, 1790, in New York City – then the nation's capital. Since the formation of the Court in 1790,

there have been only 17 Chief Justices and 98

Associate Justices (including the current Justices), with Justices serving for

an average of 15 years. On average, a new Justice joins the Court every 22

months, although sometimes the Court remains unchanged for long years (e.g. between

1994 and 2005).

The nine Justices wear black robes while in Court, and are seated by

seniority on the Bench. The Chief Justice occupies the center chair; the senior

Associate Justice sits to his right, the second senior to his left, and so on,

alternating right and left by seniority. When the Justices assemble to go on

the Bench and at the beginning of the private conferences at which they discuss

decisions, each Justice shakes hands with each of the other eight. The practice

is a reminder that despite differences of opinion on the Court, all Justices

have an overall harmony of purpose.

Courtroom seating chart of

the US Supreme Court (date May 2006)

Although Justices

are protected from political influence during their membership, politics play a

role in a president's selection of a Supreme Court justice. On average, a

president can expect to appoint two new Supreme Court Justices during four

years of office. Presidents are likely to appoint Justices whose views are

similar to their own (that is, leaning in a conservative or a liberal

direction) with the hope that these Justices will help them achieve their

political goals by passing similar-minded decisions. For example, the Supreme

Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren

(1953-69) passed a number of liberal decisions, putting an end to the

segregation of blacks and protecting the rights of women. In the 1970s, the

Court continued this practice, legalizing abortion, and extending the rights of

criminal suspects and defendants. As a result of President Ronald Reagan's appointments to the

Supreme Court during the 1980s, the Supreme Court in the last two decades has had

a small conservative majority. Many believe that this conservative majority

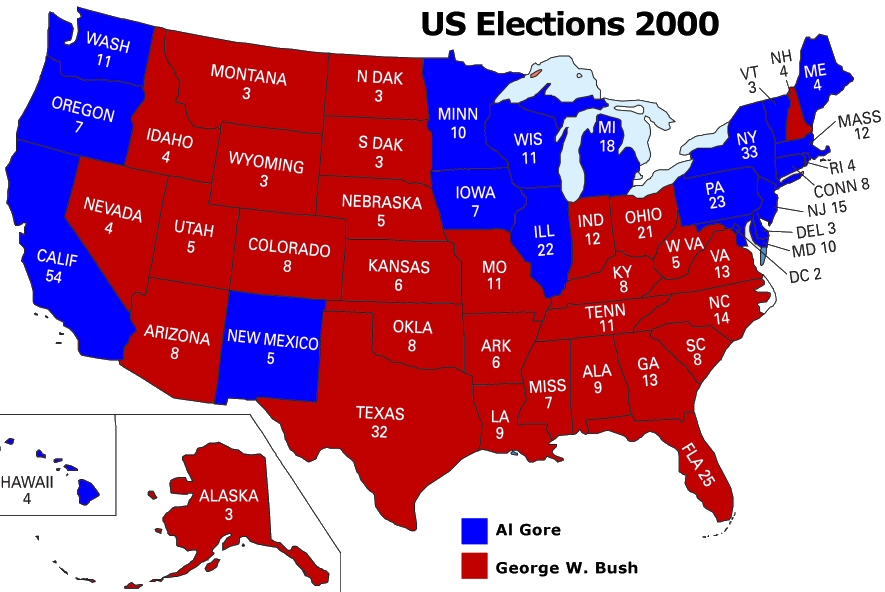

decided the legal argument after the contested 2000 Presidential election

in favour of George W. Bush.

The most recent changes (at the time of writing this text in 2006) have

occurred in late 2005 and early 2006. In September 2005, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist,

a well-known conservative, died after heading the Court for nineteen years.

President Bush replaced him with

John G. Roberts,

who had held various law-related government positions under former Republican

presidents and served two years as a judge in one of the federal Circuit Courts

of Appeal. Despite his past Republican connections, Roberts was generally

acknowledged as an outstanding jurist and was confirmed by the majority of the

Senate without much debate. Another Justice, Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female

Justice in the history of the Court, announced her retirement in the summer of

2005. Her replacement was less smooth than the replacement of the Chief

Justice: President Bush first nominated a female lawyer, a personal friend who

had no experience in either constitutional law or federal court work, so she

was critized both in public and by members of the Senate. Ultimately, she asked

the President to withdraw the nomination. Bush’s second choice was Samuel A. Alito, a US Circuit Court of

Appeal judge for 16 years, who was confirmed by the Senate in January 2006.

Alito also held government jobs during Reagan’s presidency, and is known as

moderately conservative.

In theory, the

new members of the Court have not significantly changed the internal balance of

conservatives and liberals, since both Rehnquist and O’Connor were considered

conservative, but their judicial philosophy will be truly revealed in their

practice. Out of the current nine members, there is one woman (Ruth Bader Ginsburg) and one

African-American Justice (Clarence Thomas). A

curiosity – although hardly a significant fact – of the current Court is that

for the first time in US history, the majority of the members (5 Justices) are

Catholic, including both new appointments, whereas during the history of the

Court, the great majority were Protestant.

Landmark Cases of the Supreme Court

There are a number of significant decisions made by

the Supreme Court, especially those involving constitutional questions. In the

following, there is a selection of important cases from the second half of the

20th century that have significantly influenced the life of ordinary Americans

(click on the name of each case for more detail).

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

(1954): the two most famous Supreme Court decisions concerning racial

segregation. In the former, the Supreme Court essentially ruled that racial

segregation laws in Southern states were not against the

Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution. The

Court argued that the separation of different races (in this case, separate

railway cars for whites and blacks in Louisiana) in itself was not

discrimination. The doctrine became known as „separate but equal”,

and it helped maintain legalized racial discrimination in the South for more

than half a century. This legal precedent was overturned by the Court in the

1954 decision, which ruled that racial segregation of public school children

was by definition unequal, because it created a feeling of inferiority in minority

children. As a result, black children cannot be excluded from public schools

formerly reserved for whites. This decision started the process of legal

desegregation in the South.

Engel v. Vitale (1962): Perhaps one of the most unpopular

decisions in the history of the Supreme Court, because it declared any form of

school prayer (even if it is voluntary and nondenominational) forbidden by the

„Establishment Clause” of the First Amendment of

the Constitution. The Court argued that under the

First Amendment, no federal, state or local government may approve or support

religion, and public schools are maintained by state or local governments,

therefore all forms of religious activity should be strictly excluded from

public schools. Later, the Court reinforced its strict separation of church and state

doctrine with several other controversial decisions, which remain unpopular

among the majority of Americans.

Roe v. Wade (1973): One of the most famous but also most controversial

decisions of the Court, which found that women’s right to terminate their

pregnancy by abortion is included in the right to privacy and as such, is

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision overturned a number of

state laws which had previously banned abortion except in cases when the

pregnant woman’s life was in danger. Since only the Supreme Court can change

its own precedents, liberals are worried that a Court with a conservative

majority might overturn the decision some time in the future.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) : In this decision, the Court considered

the constitutionality of racial quotas in admission to colleges and

universities, which was a widespread method of affirmative action

programs. A white man was rejected by a university medical school twice

although he had better grades than several of the black applicants who were

admitted because a certain number of places had been reserved for them. He sued

claiming that he was racially discriminated by the university. The Court passed

a rare split decision: four Justices agreed with the complaint and considered

this a violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

but four Justices accepted racial quotas as constitutional. One Justice

essentially agreed with both sides: with his vote, automatic racial quotas were

declared unconstitutional, but the Court also ruled that race can be used as „a

criterion” in admission. Since then, affirmative action policies have

repeatedly been attacked in courts and have been much reduced in scope.

Mapp v. Ohio (1961): The Court’s decision in this case

established the so-called

exclusionary

rule, which means that no evidence may be used in a trial which has been

obtained in an illegal way. In other words, the police authorities may not

search a suspect’s home or private property without a proper search warrant

issued by a judge. If they do, and they actually find something that could be

used against the suspect, such evidence must be excluded from the trial. This

rule is one of the major protections of the rights of criminal suspects, based

on the Fourth Amendment.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966): This decision significantly changed the

procedure against criminal suspects, since the Court ruled that all suspects

have a right to be informed about their constitutional rights to remain silent

during interrogation and to have counsel (a lawyer) present. If the police or

prosecutors receive statements from suspects who have not been informed about

these rights, such statements cannot be used as evidence in the trial. In other

words, police cannot extort admissions from suspects using psychological

pressure while keeping them isolated from a lawyer. After the decision, it has

become standard practice to read out the rights of a suspect immediately on

arrest: it is called the Miranda warning, often seen and heard

in many American movies („You have the right to remain

silent. If you give up that right, anything you say can and will be used

against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney and to have an

attorney present during questioning. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will

be provided to you at no cost. During any questioning, you may decide at any

time to exercise these rights, not answer any questions, or make any

statements.”).

Furman v. Georgia (1972): In this decision, the Court was asked to

decide whether capital punishment

falls under the „cruel and unusual punishment” category forbidden by the

Eighth Amendment of the

Constitution.

Although the majority of the Court did not rule capital punishment itself

unconstitutional, they observed that the death penalty is often imposed

unfairly in many states. People are convicted to death for relatively less

severe crimes, on the basis of uncertain evidence, and disproportionately many

blacks are convicted. This decision led to the revision of death penalty laws and procedural rules in most states.

Although the

Constitution, as

its Preamble boldly stated, was written in the name of „We the People of the

United States”, the Founding Fathers did not give the citizens of the country

full democratic control over the federal government. In the original

Constitution, only the lower house of Congress was elected by

the people; the selection of Senators as well as the electors responsible for

electing the President (see below) was left to the state legislatures. And even

the Representatives were not elected by all the adult population of each

district: each state had laws that restricted the franchise (the right to vote;

also called

suffrage) to property-owning or taxpaying adult

males. All women as well as all black males were excluded from the franchise,

even in those states where slavery did not exist.

The democratic principle – the idea that all adults

should have the right to participate in elections – gradually gained ground

during the 19th century. By the mid-19th century, property qualifications were

gradually abolished in all states, so all white male adults received the

franchise. After the Civil War, the

15th Amendment was

added to the Constitution in 1870, which was meant to

guarantee the rights of former slaves to vote (it is another matter that most

blacks remained disfranchised in the Southern states until the civil rights movement

of the 1950s and 60s). And the 19th Amendment in

1920 gave the franchise to all adult women. Finally, the

26th Amendment in 1971 lowered the minimum voting age from 21 to 18 (as a result,

young Americans between 18 and 21 today may vote but may not legally buy and

drink alcohol).

Today, federal

elections are partly governed by the

Constitution and federal laws, and partly by state laws. Each state is free to set

its own election laws as long as they do not contradict the

Constitution or existing federal laws. As a result, the rules

of federal elections are not uniform all over the country. For example, some

states do not allow felons (people serving a prison sentence for a major crime)

to vote, while others do. Unlike

in Hungary, there is no federal or central

database of voters, where their addresses are stored and regularly updated:

people who wish to vote at an election are required to

register first in their home state by identifying themselves and

giving their current address. Since registration is not compulsory, a

significant number of people never bother to register themselves, and as a

result, they never vote. Non-registration is especially common among poor and

uneducated people and ethnic minorities. Before the 1970s, registration was

also an effective way to exclude blacks from elections in the southern states,

because the authorities refused to register them on various legal excuses.

in Hungary, there is no federal or central

database of voters, where their addresses are stored and regularly updated:

people who wish to vote at an election are required to

register first in their home state by identifying themselves and

giving their current address. Since registration is not compulsory, a

significant number of people never bother to register themselves, and as a

result, they never vote. Non-registration is especially common among poor and

uneducated people and ethnic minorities. Before the 1970s, registration was

also an effective way to exclude blacks from elections in the southern states,

because the authorities refused to register them on various legal excuses.

Various states also have different methods for

voting and counting the votes.

In Hungary and most European countries, voting

is typically done with a pen on a paper ballot: the

ballot contains the names of all the candidates for the office, and

the voter puts a cross into a box next to the candidate’s name. Then votes are

counted by hand. In the US, however, voting is usually done by special voting

machines, which make counting faster and easier. In the 1960s, the punchcard

system was introduced: voters are given a standard-sized punchcard and a punch

device, and they punch a hole next to the name of the candidate they prefer.

The votes on the punchcards are then counted by special machines. Nowadays,

punchcard systems are still the most widespread in the US. Other systems

include optical scanning (voters darken a field next to the candidate’s name on

the ballot card, and an optical device counts votes by scanning the dark field

of each card) or computerized electronic voting (voters make their choice on a

touch-screen or by pushing buttons on a keyboard, and votes are added up by the

computer). From the voters’ point of view, the easiest and quickest system is

electronic voting, but many states distrust computers because they can be

manipulated and there is no way to recount the votes in case the outcome is

disputed.

In Hungary and most European countries, voting

is typically done with a pen on a paper ballot: the

ballot contains the names of all the candidates for the office, and

the voter puts a cross into a box next to the candidate’s name. Then votes are

counted by hand. In the US, however, voting is usually done by special voting

machines, which make counting faster and easier. In the 1960s, the punchcard

system was introduced: voters are given a standard-sized punchcard and a punch

device, and they punch a hole next to the name of the candidate they prefer.

The votes on the punchcards are then counted by special machines. Nowadays,

punchcard systems are still the most widespread in the US. Other systems

include optical scanning (voters darken a field next to the candidate’s name on

the ballot card, and an optical device counts votes by scanning the dark field

of each card) or computerized electronic voting (voters make their choice on a

touch-screen or by pushing buttons on a keyboard, and votes are added up by the

computer). From the voters’ point of view, the easiest and quickest system is

electronic voting, but many states distrust computers because they can be

manipulated and there is no way to recount the votes in case the outcome is

disputed.

In 1845, Congress set the date of Congressional and

Presidential elections on the Tuesday following the first Monday of November in

even-numbered years, called simply

Election

Day in the US. Many states, although not all of them, hold several of their

elections (e.g. election of the state governor or members of the state

legislature) also on this day, to make use of the high voter turnout.

Primaries

In the US, basically anybody who may vote may also

be a candidate for any political

office, including Congress seats.

They do not need to collect "nomination slips" ( kopogtatócédula) from voters

like in Hungary, or deposit a certain amount of money, as in Britain: all they

need to do is announce their intention and register their name with the

authority that organizes the election. In most cases, however, only the

candidates of the two largest parties have a realistic chance to win a seat in

either house of Congress. It is a very important aspect of American democracy

that the candidates of the two parties are not appointed by state or national

party leaders, but they are also chosen by the voters. The system of selecting

the most popular party candidate is called

primary

election in the US.

kopogtatócédula) from voters

like in Hungary, or deposit a certain amount of money, as in Britain: all they

need to do is announce their intention and register their name with the

authority that organizes the election. In most cases, however, only the

candidates of the two largest parties have a realistic chance to win a seat in

either house of Congress. It is a very important aspect of American democracy

that the candidates of the two parties are not appointed by state or national

party leaders, but they are also chosen by the voters. The system of selecting

the most popular party candidate is called

primary

election in the US.

Primary elections were first introduced in the

early 20th century, to put an end to the corrupt practice of party bosses

choosing their loyal followers to run for offices. The purpose of a primary is to

decide which candidate of a certain party should be nominated for a certain

office. It is basically a small election within each party.

There are different kinds of primary elections. At

a closed primary, only those people

may vote on a certain party’s candidates who have registered themselves as

party supporters. This kind of primary can be seen as an opinion poll among

party supporters. At an open primary,

however, any local resident may vote for either party’s candidates (though not

for both at the same time), regardless of their party affiliation. An open

primary tries to find out which party candidate is the most popular among the

general population, rather than merely among party supporters. The winners of

the two parties’ primaries then try to defeat each other in November. Primary

elections are the most complicated during presidential campaigns, because the

president is the only office-holder elected nationwide, therefore all 50 states

must hold primaries or caucuses

(another, older and less widespread way of expressing preference for one of the

candidates, where people vote publicly, not by secret ballot, as in primaries).

The winner-take-all rule

Most elections in the US are decided on the basis

of the

winner-take-all rule, which

simply means that the candidate with the most votes wins. In other words, there

is no requirement to achieve an absolute

majority (50% + 1 vote), it is enough to have a plurality of the votes (to receive more votes than any of the other

candidates). The system has one big advantage: it is simple and easy to

understand for everybody. Under the winner-take-all system, there is no need

for a runoff election (a second round), because somebody always ends up as

winner (except when two winners receive exactly the same number of votes, but

that is very unlikely). Its disadvantage is, however, that it allows somebody

to win who does not enjoy the support of the majority of voters. The

winner-take-all rule may produce especially strange results at presidential

elections, because under certain circumstances it allows the candidate who has

received less votes nationwide to win the election and become president (see

below).

Members of the the House of Representatives are elected every second year. Representatives may be re-elected as

many times as they wish. There are 435 seats in the House, which are

apportioned (distributed) among the 50 states in proportion to their

population, and re-apportioned every 10 years after a new national census (see

Congress).

The Constitution prescribes, however, that each

state must have at least one Representative in

Congress,

regardless of how small their population is. Federal laws also require that the

states divide their territory into

Congressional

districts of equal population, and each district should elect one

Representative into the House. Each state legislature is free, however, to draw

the boundaries of its districts any way they wish, which gives opportunity for

political manipulation. The party which has a majority in the state legislature

usually tries to draw the boundaries in such a way as to include a majority

preferring their party in as many districts as possible. This manipulation is

called

gerrymandering in American

English.

Senators are elected for six-year terms, and they may also

be re-elected as many times as they wish. Each state, regardless of its size or

population, has two Senators, who are never re-elected at the same time. Every

second year, about one-third of the 100 Senators are re-elected. Senators are

always elected by all the voters of the state.

Under the two-party system, the typical

choreography of Congressional elections is the following: there is an incumbent, a person currently in office

who enjoys the support of one party. This person is challenged by the candidate

of the other party who would like to defeat them. So one candidate is fighting

to keep their seat in Congress, while the other is struggling to take it away

from them. The only exception to this rule is when the incumbent dies or

decides to retire, and both parties need to find a new candidate for the

position.

Presidential Campaigns

The longest, hardest and most complicated election campaign precedes the election of the

President. Since the President is the only federal official elected by the

entire nation, the selection of the most suitable candidate in itself takes a

long time. More than a year before Election Day, the summer or fall of the

previous year, several people in both parties announce their intention to „run

for President”, as people on the street say.

There are two types of situation, depending on

whether the current President is finishing his first or his second term in office. If he has been in

office only for one term, he is most likely to run again, and in this case he

is usually not challenged by anybody else from his party (the last President

who could have run for a second term and decided not to do so was Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968, because his

popularity hit rock bottom due to the unsuccessful Vietnam War). If the President is

finishing his second and last term, however, the race is open for candidates in

both parties: such a situation occurred in 1988, when Ronald Reagan ended his second term, or in

2000, when Bill Clinton did

so, and the same situation is coming in 2008, when George W. Bush is going to step down after

eight years in office.

After a candidate has announced his wish to become

President, he or she first needs to collect a huge amount of money, usually

millions of dollars, because the campaign is extremely costly. Each of the

presidential candidates need dozens of campaign

managers, advisers, aides, assistants, and a nationwide

network of – partly voluntary – activists in order to have a chance for

success. Most of the money, however, is spent on political advertisement. In

the US, there are no legal limits on political ads in the public media, and

prices are very high, especially as presidential candidates have to reach a

nationwide audience. Donations may come from individuals or organizations, but

the maximum amount is limited by law in order to prevent candidates from

becoming too indebted to any one supporter. There are various loopholes,

however, which make it possible for candidates to collect more money than the

laws allow; such semi-legal income is called ’soft money’ in American political slang, and it often amounts to

millions of dollars.

The campaign really begins in January of the

election year, when the so-called primary

season starts: this is the period of time during which both parties hold

their presidential primaries in all the states. During this period (usually

between late January and early June), the number of presidential candidates in

each party is reduced from as many as ten or more to two or one. The long

series of primary elections have one purpose: to select the most popular

candidate in both parties. If a current President runs again, his party usually

does not hold primaries at all, or even if it does, it is only a formality. But

when the incumbent President retires, both parties need a full series of

primary elections to select the party’s candidate.

At presidential primaries, voters formally elect

not candidates but delegates to the

party’s nominating convention. Nonetheless, the delegates are bound to

represent the preference of voters expressed at the primary. Apart from this

general rule, there is a lot of variety from state to state. Some states prefer

the caucus system instead of primaries (in 2004, for example, Democratic party

organizations in 15 states held caucuses, while 35 of them had primaries). Each

state has its own primary rules: how to vote (see open and closed

primaries),

how to distribute delegates among candidates (interestingly, the

winner-take-all principle is not applied at primaries, so candidates finishing

second or third at a state primary also gain some delegates) etc. Each state is

free to set the date of its primary, but within each state, both parties have

their primaries at the same time. The earliest primary is traditionally held in

New Hampshire in late January or early

February, under a lot of national media attention. After that, primaries

continue until early summer, but the later primaries attract much less

attention, because in most cases, the probable winner emerges by March the

latest. If there is a clear favorite among the candidates, and he keeps winning

more and more primaries, the rivals gradually realize that they have no chance

to defeat him at the convention, and one by one, they decide to give up the

race. Despite the disappearance of the rivals, however, the winner of the

primary season becomes the party’s official candidate only when he is announced

at the convention.

Both parties’

nominating

conventions are usually held in late summer, typically in August.

Conventions are the closest equivalent to the party congresses of European

parties, because this is the only occasion that the two big parties have a

national gathering, but they take place only once every four years. Their most

important task is to officially choose and nominate the party’s presidential

candidate. In the past, the nomination was often decided only at the convention

itself with the delegates voting for their favorite, but no party convention

had more than one standing candidate since 1976 (in that year, Gerald Ford defeated Ronald Reagan at the Republican

convention). The other important event of the convention is that the candidate

announces his choice for Vice-President. The vice-presidential candidate is always picked by the presidential

candidate out of the party’s politicians. Very often, he invites one of his

rivals from the primary season, who lost against him in the nomination race.

The two candidates form the so-called presidential

ticket: voters are two choose between two pairs of candidates on Election

Day. Vice-presidential candidates are usually selected in such a way as to

bring more votes for the ticket: if the presidential candidate is from the East

Coast, he may pick someone from the South or the West; if he is relatively old,

he may choose a younger person; and so on. Afterwards, the two candidates continue

the campaign together, and the vice-presidential nominee also works hard for

the success of the ticket.

Besides these two important announcements,

conventions are typically spectacular media events, where all the leading

figures of the party make speeches, pledge their support for the party’s

candidate, and encourage voters to do the same. Well-known entertainers

(singers, musicians, actors etc.) and other national celebrities also appear

regularly. Members of the audience are waving signs with the candidates’ names

(e.g. „Bush & Cheney for President!”), they applaude and cheer a lot, so

the whole thing is essentially a national political show to attract more voters

to the party’s candidates.

After the conventions, the last and most important

period of the campaign begins, when there are only two candidates (and two

vice-presidential candidates) left, and both parties unite in their effort to

secure the presidency for them. In this period, the candidates continue to tour

the whole country, attending public rallies,

giving countless speeches and interviews. Since the 1970s, the candidates have

always had televised debates, which

are considered crucial for the outcome of the election. The rules and

conditions are carefully set before the event begins: both candidates must

receive the same amount of time to talk, the moderator must be perfectly

neutral, the audience (if there is any) is forbidden to clap or express

preference for any candidate. Since there are a significant number of voters

who do not make up their mind until the last weeks of the long campaign, the

good or bad appearance made by one or the other candidate at the televised

debates may determine the outcome of the whole election.

Presidential Elections

The Founding Fathers worked out an indirect

method for the election of the President. According to the

Constitution, each state should select as many electors as the number of Congressmen

(Representatives + Senators) they have in the federal Congress (but electors

must not be identical with the state’s Congressmen). These electors gather in

each state capital and vote for president and vice president, and their votes

are sent to Washington D.C. The person who receives an absolute majority (that

is, at least 50% +1 vote) from all the electors becomes President. In case

nobody receives an absolute majority, the House of Representatives can elect

the President out of the three best candidates in such a way that each state

has one vote in the House. Today, since there are 435 members of the House and

100 members of the Senate, plus

Washington D.C. (which does not belong

to any state) is also given 3 electors (23rd Amendment,

1961), there are altogether 538 electoral votes, and 270 votes are needed for

any candidate to be elected President.

The Constitution

remains silent on whether the electors of each state should be elected by the

people or not. The Founding Fathers

apparently thought that this issue should be left to the states to decide. At

the earliest presidential elections, several of the states held popular

elections and gave their electors a mandate to follow the popular will; while

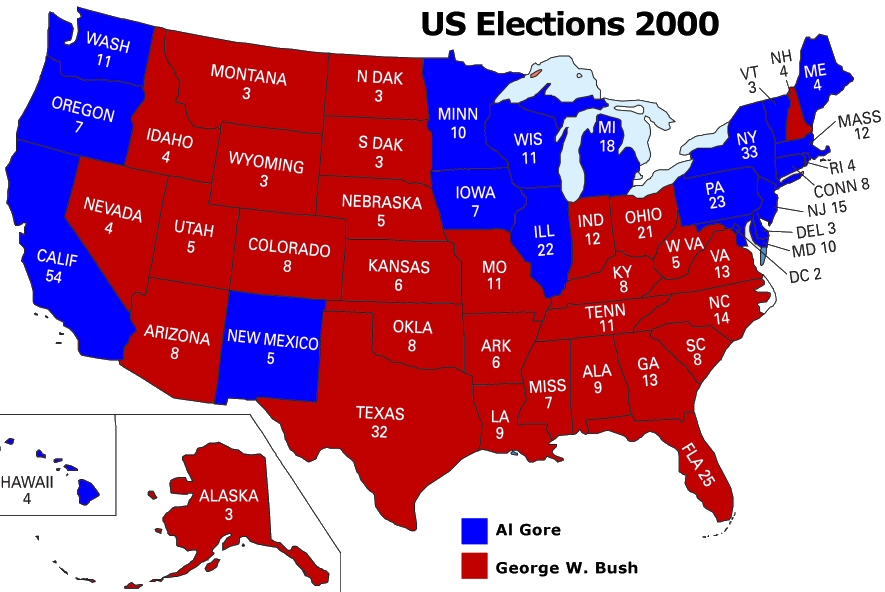

in several other states, the legislatures selected their electors and told them